Dis Model Mech. 2017 May 1; 10(5): 551–558.

doi: 10.1242/dmm.028373

PMCID: PMC5451172

PMID: 28069688

Upregulation of CB2 receptors in reactive astrocytes in canine degenerative myelopathy, a disease model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

María Fernández-Trapero,1,2,3,4,* Francisco Espejo-Porras,1,2,3,* Carmen Rodríguez-Cueto,1,2,3 Joan R. Coates,5 Carmen Pérez-Díaz,4 Eva de Lago,1,2,3,§ and Javier Fernández-Ruiz1,2,3,§

Author information ► Article notes ► Copyright and License information ► Disclaimer

This article has been cited by other articles in PMC.

Go to:

ABSTRACT

Targeting of the CB2 receptor results in neuroprotection in the SOD1G93A mutant mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). The neuroprotective effects of CB2 receptors are facilitated by their upregulation in the spinal cord of the mutant mice. Here, we investigated whether similar CB2 receptor upregulation, as well as parallel changes in other endocannabinoid elements, is evident in the spinal cord of dogs with degenerative myelopathy (DM), caused by mutations in the superoxide dismutase 1 gene (SOD1). We used well-characterized post-mortem spinal cords from unaffected and DM-affected dogs. Tissues were used first to confirm the loss of motor neurons using Nissl staining, which was accompanied by glial reactivity (elevated GFAP and Iba-1 immunoreactivity). Next, we investigated possible differences in the expression of endocannabinoid genes measured by qPCR between DM-affected and control dogs. We found no changes in expression of the CB1 receptor (confirmed with CB1 receptor immunostaining) or NAPE-PLD, DAGL, FAAH and MAGL enzymes. In contrast, CB2 receptor levels were significantly elevated in DM-affected dogs determined by qPCR and western blotting, which was confirmed in the grey matter using CB2 receptor immunostaining. Using double-labelling immunofluorescence, CB2 receptor immunolabelling colocalized with GFAP but not Iba-1, indicating upregulation of CB2 receptors on astrocytes in DM-affected dogs. Our results demonstrate a marked upregulation of CB2 receptors in the spinal cord in canine DM, which is concentrated in activated astrocytes. Such receptors could be used as a potential target to enhance the neuroprotective effects exerted by these glial cells.

KEY WORDS: Cannabinoids, Endocannabinoid signaling, CB2 receptors, Canine degenerative myelopathy, Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, SOD1, Activated astrocytes

Go to:

INTRODUCTION

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a progressive degeneration and loss of upper and lower motor neurons in the brain and spinal cord, causing muscle weakness and paralysis (Hardiman et al., 2011). In 1993, genetic studies identified the first mutations in the copper-zinc superoxide dismutase gene (SOD1), which encodes a key antioxidant enzyme, SOD1 (Rosen et al., 1993). Mutations in SOD1 account for 20% of genetic ALS and 2% of all ALS. More recently, similar studies have identified mutations in other genes, such as TARDBP (TAR-DNA binding protein) and FUS (fused in sarcoma), which encode proteins involved in pre-mRNA splicing, transport and/or stability (Buratti and Baralle, 2010; Lagier-Tourenne et al., 2010) and, in particular, the CCGGGG hexanucleotide expansion in the C9orf72 gene, which appears to account for up to 40% of genetic cases (Cruts et al., 2013). Their pathogenic mechanisms, which differ, in part, from the toxicity associated with mutations in SOD1, led to a novel molecular classification of ALS subtypes (Al-Chalabi and Hardiman, 2013; Renton et al., 2014).

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a progressive degeneration and loss of upper and lower motor neurons in the brain and spinal cord, causing muscle weakness and paralysis (Hardiman et al., 2011). In 1993, genetic studies identified the first mutations in the copper-zinc superoxide dismutase gene (SOD1), which encodes a key antioxidant enzyme, SOD1 (Rosen et al., 1993). Mutations in SOD1 account for 20% of genetic ALS and 2% of all ALS. More recently, similar studies have identified mutations in other genes, such as TARDBP (TAR-DNA binding protein) and FUS (fused in sarcoma), which encode proteins involved in pre-mRNA splicing, transport and/or stability (Buratti and Baralle, 2010; Lagier-Tourenne et al., 2010) and, in particular, the CCGGGG hexanucleotide expansion in the C9orf72 gene, which appears to account for up to 40% of genetic cases (Cruts et al., 2013). Their pathogenic mechanisms, which differ, in part, from the toxicity associated with mutations in SOD1, led to a novel molecular classification of ALS subtypes (Al-Chalabi and Hardiman, 2013; Renton et al., 2014).

The ultimate goal in ALS is to develop novel therapeutics that will slow disease progression. Rilutek has been the only drug approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), but it is limited in efficacy (Habib and Mitsumoto, 2011). Recently, cannabinoids have been shown to have neuroprotective effects in transgenic rodent ALS models (Bilsland and Greensmith, 2008; de Lago et al., 2015, for review). Chronic treatment with the phytocannabinoid Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-THC) delayed motor impairment and improved survival in the SOD-1G93A transgenic mouse (Raman et al., 2004). Other cannabinoid compounds, including the less psychotropic plant-derived cannabinoid cannabinol (Weydt et al., 2005), the non-selective synthetic agonist WIN55,212-2 (Bilsland et al., 2006), and the selective cannabinoid receptor type-2 (CB2) agonist AM1241 (Kim et al., 2006; Shoemaker et al., 2007), produced similar effects. Genetic or pharmacological inhibition of fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH), one of the key enzymes in endocannabinoid degradation, was also beneficial in SOD1G93A transgenic mice (Bilsland et al., 2006). The efficacy shown by compounds that target the CB2 receptor (Kim et al., 2006; Shoemaker et al., 2007) appears to be facilitated by the fact that this receptor is upregulated in reactive glia in post-mortem spinal cord tissue from ALS patients (Yiangou et al., 2006). Such elevation of CB2 receptors has been also described in SOD1G93A transgenic mice (Shoemaker et al., 2007; Moreno-Martet et al., 2014), and we recently found that the response occurred predominantly in activated astrocytes recruited at lesion sites in the spinal cord (F.E.P., unpublished results). We have also described a similar increase in CB2 receptors on reactive microglia in TDP-43 transgenic mice (Espejo-Porras et al., 2015). Based on these studies, the CB2 receptor may be a novel target in altering disease progression in ALS, given its effective control of glial influences exerted on neurons, as investigated in other disorders (Fernández-Ruiz et al., 2007, 2015; Iannotti et al., 2016 for review).

A challenge of preclinical studies of novel neuroprotective agents in ALS is poor translation of therapeutic success in small animal (e.g. rodents, zebrafish, flies, nematodes) to human ALS patients. Most studies have been based on overexpression of specific human gene mutations. In this context, we have recently turned to canine degenerative myelopathy (DM), a multisystem central and peripheral axonopathy described in dogs in 1973 (Averill, 1973), with an overall prevalence of 0.19% (Coates and Wininger, 2010 for review), which shares pathogenic mechanisms with some forms of human ALS, including mutations in SOD1 as one of the major causes of the disease (Awano et al., 2009). With some differences depending on the type of breed, DM is characterized by degeneration in the white matter of the spinal cord and the peripheral nerves, which progresses to affect both upper and lower motor neurons (Coates and Wininger, 2010 for review). The disease appears at 8-14 years of age with an equivalent effect in both sexes that necessitates euthanasia (Coates and Wininger, 2010 for review). This canine pathology represents a unique opportunity to investigate ALS in a context much closer to the human pathology, using an animal species that are phylogenetically closest to humans, and in which the disease occurs spontaneously. Our objective in the present study has been to investigate the changes that the development of DM produces in endocannabinoid elements in those CNS sites (spinal cord) most affected in this disease. It is important to note that such elements may result in potential targets for a pharmacological therapy with cannabinoid-based therapies (e.g. Sativex) aimed at delaying/arresting the progression of the disease in these dogs, and ultimately in humans. The study was carried out with post-mortem tissues (spinal cords) from dogs affected by DM kindly provided by Dr Joan R. Coates (University of Missouri, Columbia, MO, USA) and classified in different disease stages (Coates and Wininger, 2010). All DM tissues included the necessary clinical, genetic and neuropathological information, and they were accompanied by adequate matched control tissues. Both DM-affected and control tissues were used for analysis of endocannabinoid receptors and enzymes using biochemical (qPCR, western blot) and, in some cases, histological (immunohistochemistry) procedures, including the use of double immunofluorescence staining to identify the cellular substrates in which the changes in endocannabinoid elements (CB2 receptors) take place.

Go to:

RESULTS

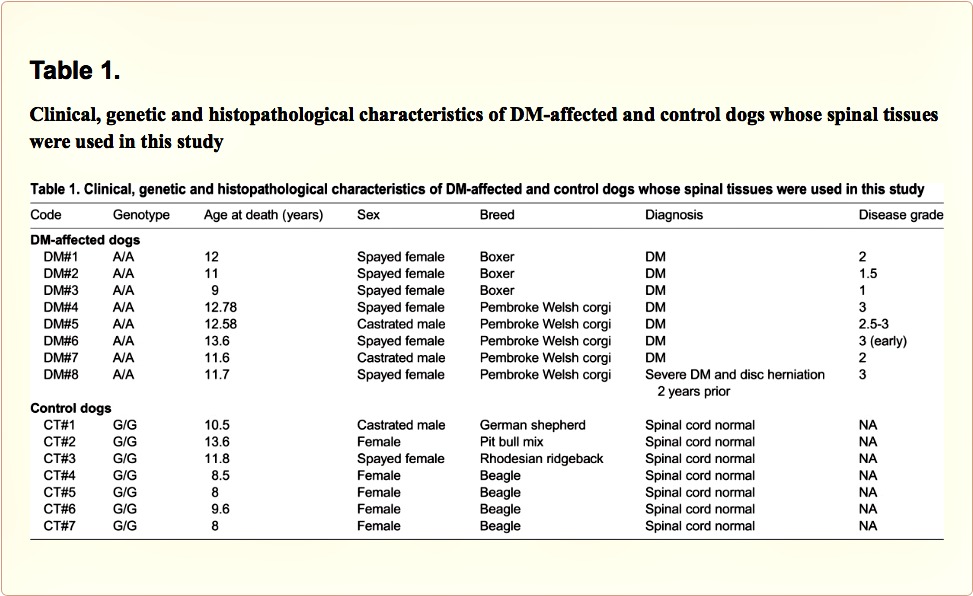

Validation of the expected histopathological deterioration in DM-affected dogs

The data provided by the biobank confirmed that all tissues obtained from DM-affected dogs had a clinical diagnosis of DM in all cases supported by the genetic analysis which confirmed the presence of the SOD1 mutation. They corresponded to two different breeds, which are from species most affected by this disease (Coates and Wininger, 2010), and animals were all euthanized in an age interval of 9-13.6 years (11.8±0.6; mean±s.d.), with a grade of the disease of 1-3 (2.2±0.3). DM-affected dogs included 6 spayed females and 2 castrated males (see details in Table 1). The control tissues were selected from dogs with no clinical diagnosis of DM. All control dogs were homozygous wild-type and age-matched (8-13.6 years; 10.0±0.8). They included 6 females, 1 of them spayed, and 1 castrated male (see details in Table 1).

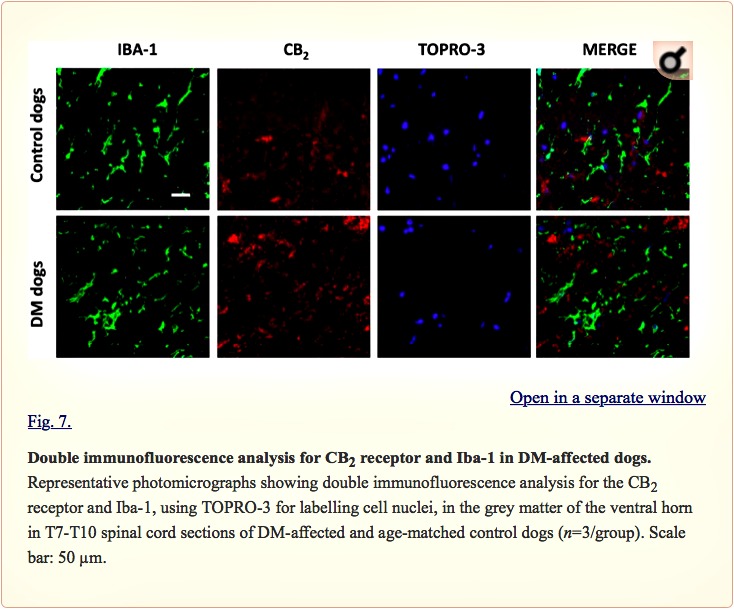

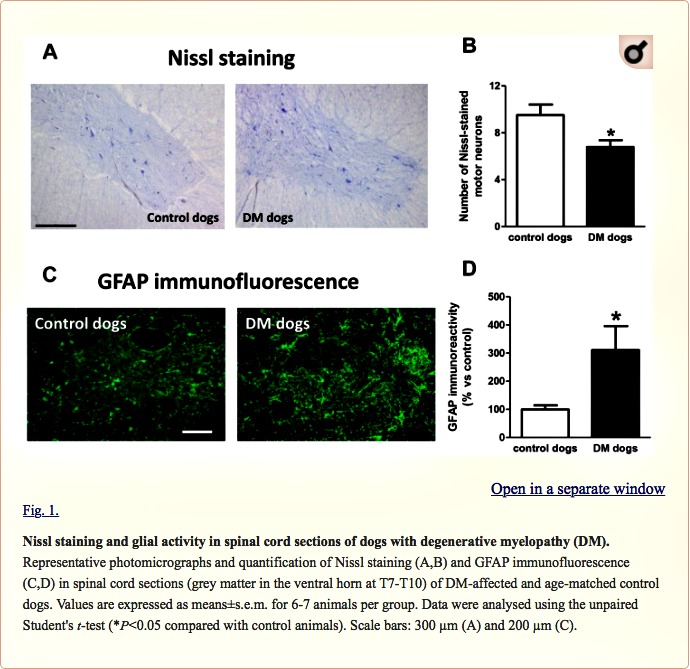

We found a significant reduction in the number of Nissl-stained cell bodies corresponding to lower motor neurons located in the ventral horn of DM-affected spinal cords (Fig. 1A,B). The neuronal loss was accompanied by an intense glial reactivity in the affected areas, in particular, we detected a 3-fold increase in GFAP immunolabelling in the spinal grey matter (Fig. 1C,D). We also found microgliosis in both white and grey matter of the spinal cord, detected with DAB immunostaining for the microglial marker Iba-1 (Fig. 2A); Iba-1 levels were increased 2.5-fold in the grey matter of DM-affected dogs compared with levels in control dogs (Fig. 2B,C).

Changes in the endocannabinoid receptors and enzymes in DM-affected dogs

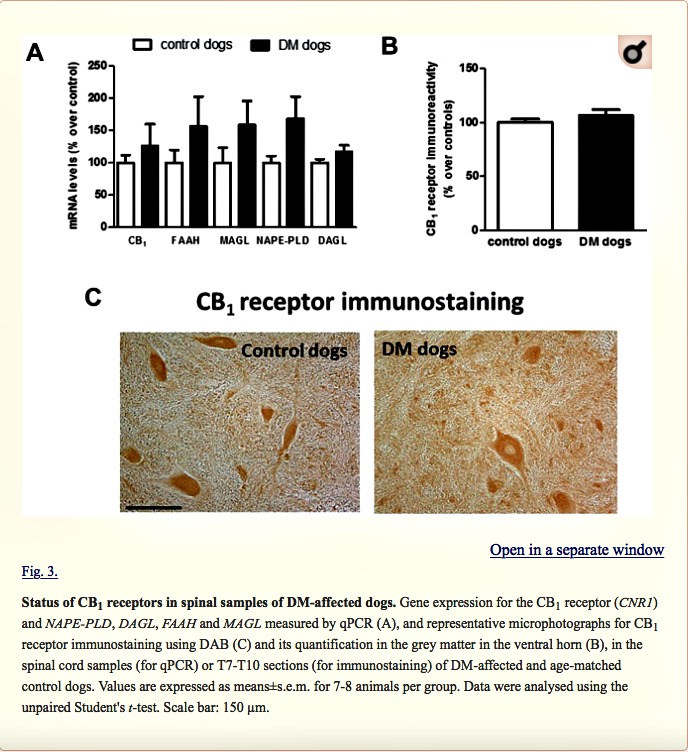

Next, we investigated possible differences between DM-affected dogs and control animals in the expression of endocannabinoid genes measured by qPCR. Although there was a trend towards an elevation, there were no significant changes in expression of the CB1 receptor (CNR1), or FAAH, monoacylglcerol lipase (MAGL), N-arachidonoyl-phosphatidylethanolamine phospholipase D (NAPE-PLD) and diacylglycerol lipase (DAGL) enzymes between the two groups (Fig. 3A). We attempted to determine whether the trends detected for these five parameters may correspond to a greater effect in DM dogs with advanced disease, but we did not find any statistically significant correlation (data not shown). They were not related to gender-dependent differences (data not shown). The absence of changes in CB1 receptor gene expression was observed at the protein level using DAB immunostaining in the grey matter (Fig. 3B,C). This occurred despite the reduction in the number of motor neurons detected with Nissl staining.

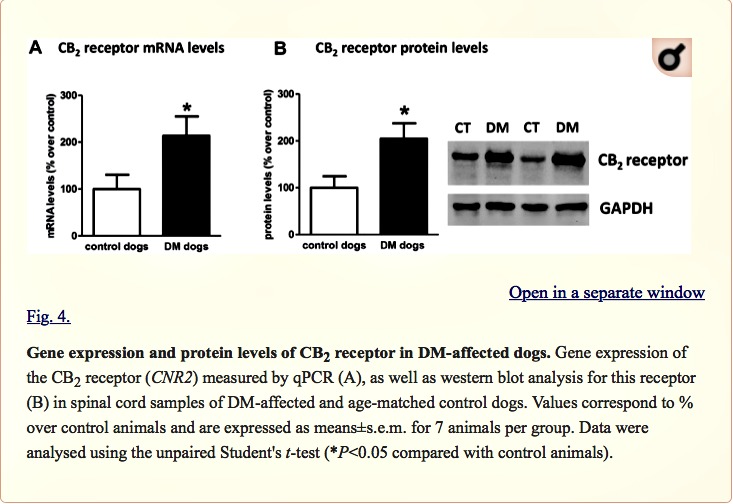

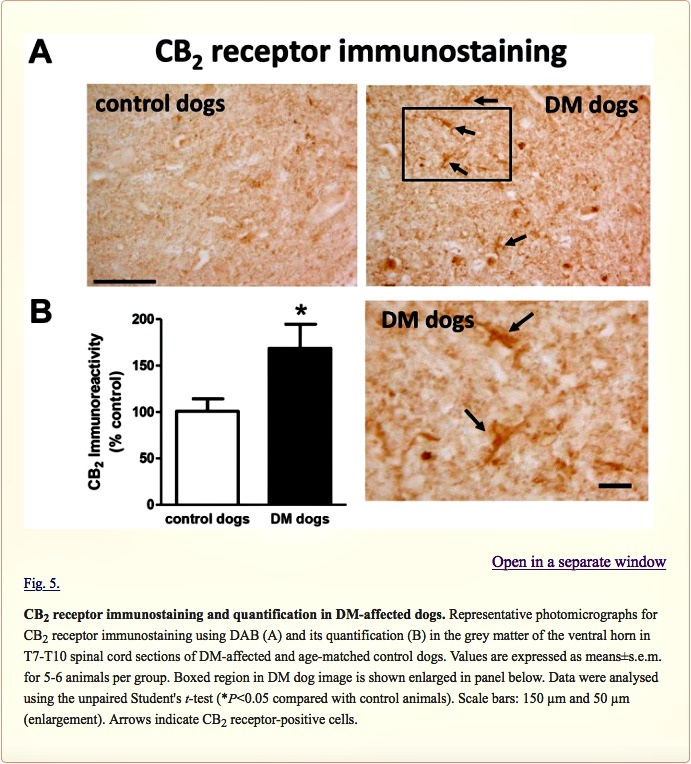

Next, we investigated the CB2 receptor, an endocannabinoid element that is frequently altered in conditions of neurodegeneration (Fernández-Ruiz et al., 2007, 2015; Iannotti et al., 2016), including ALS (Yiangou et al., 2006; Shoemaker et al., 2007; Moreno-Martet et al., 2014; Espejo-Porras et al., 2015). First, we detected an increase of more than 2-fold in CB2 receptor (CNR2) expression, measured by qPCR, in DM-affected dogs (Fig. 4A). We also investigated whether this increase occurred predominantly in the tissues obtained from DM-affected dogs at the intermediate and advanced stages, but we did not find any significant correlation between both variables (data not shown). This increase in gene expression was confirmed at the protein level using western blotting (2-fold increase; Fig. 4B), as well as using DAB immunostaining, which showed that the number of CB2 receptors increased predominantly in the grey matter (Fig. 5A,B).

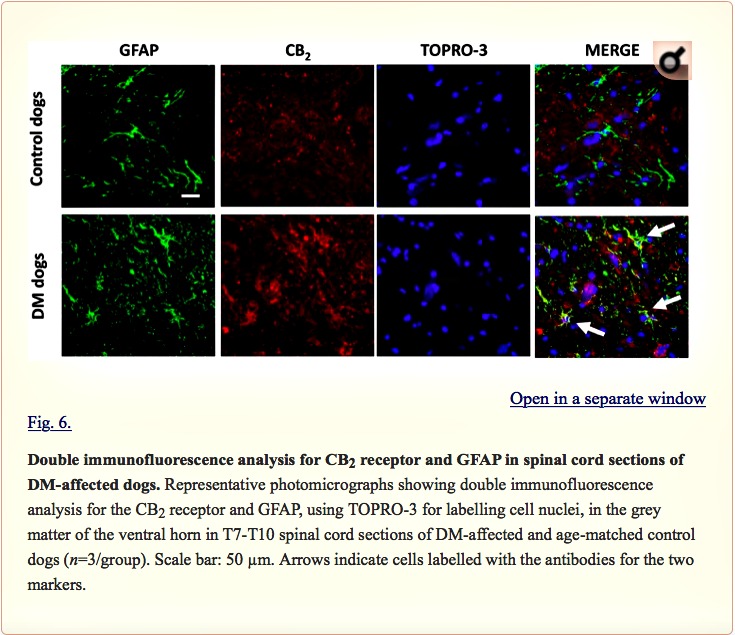

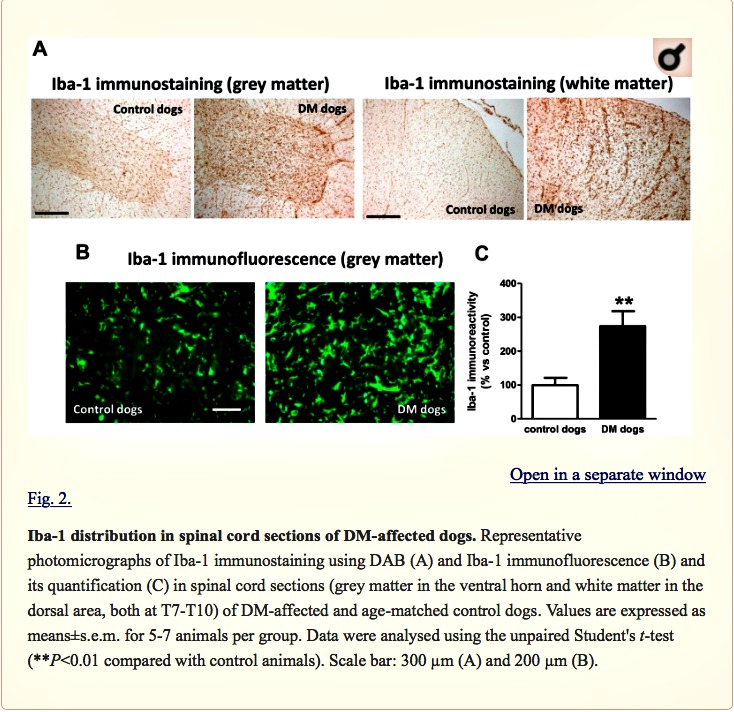

Double-labelling analyses to identify the CB2 receptor-positive cellular substrates

Examination of the morphology of those cells positive for the CB2 receptor in DAB immunostaining (Fig. 5A) suggested they were glial cells. We wanted to confirm this by using double-labelling immunofluorescence analysis. We found that CB2 receptor immunolabelling colocalized with GFAP immunofluorescence (Fig. 6), thus indicating that the upregulation of CB2 receptors in the spinal cord of DM-affected dogs occurred in reactive astrocytes. Similar double-labelling immunofluorescence with Iba-1 did not detect any colocalization with the CB2 receptor immunostaining, indicating that the receptor is not located in microglial cells in the spinal cord of DM-affected dogs (Fig. 7).

Articles from Disease Models & Mechanisms are provided here courtesy of Company of Biologists