Learn more: PMC Disclaimer | PMC Copyright Notice

. 2024 Oct 25;11(10):e70063. doi: 10.1002/nop2.70063

ABSTRACT

Aims

This study aimed to describe nurses’ experiences caring for patients who use medicinal cannabis. For the purpose of this study, the term ‘medicinal cannabis’ is used to describe cannabis‐based products that are sourced legally or illegally.

Design

Qualitative study using thematic analysis.

Methods

Eleven registered nurses explored their experiences caring for patients using medicinal cannabis in the Australian healthcare sector. Semistructured interviews were via telephone, Zoom or face to face. Transcribed interview data were analysed using the six phases of thematic analysis.

Results

The nurses’ experiences of caring for patients who use medicinal cannabis were described in three themes; ‘Searching for predictable processes of regulation, access and use of medicinal cannabis’, ‘One conundrum after another’ and ‘There is a lot to learn’. Overall, nurses described feeling underprepared to care for patients who use or want to use medicinal cannabis in the Australian healthcare sector.

Conclusion

The results indicate that nurses want to have meaningful discussions with patients about the use of medicinal cannabis, yet do not always have the confidence to do so. Nurses sought their own education on how to better support patients. All participants echoed the need for education. The nurse’s role in caring for and supporting patients using medicinal cannabis could improve the patient experience.

Implications for the Profession and/or Patient Care

Nurses play an essential role in improving the patient’s experience and advocating for those using or wanting to discuss medicinal cannabis as a part of holistic care. Defining the nurse’s role in effectively caring for patients can begin by providing evidence‐based education to nurses. Including nurses in policy development and beginning to understand the legal and regulatory implications for nurses are important.

Impact

This is the first study presenting current issues for nurses who care for patients using medicinal cannabis in Australian healthcare systems.

Reporting Method

COREQ guidelines were adhered to for this study.

No Patient or Public Contribution

For this research project on the experiences of registered nurses caring for patients using medicinal cannabis, we did not engage members of the patient population or the general public.

1. Introduction

Medicinal cannabis has historically been one of the most widely used drugs, legally and illegally, because of its medicinal effects (Sinclair et al. 2020). Legalisation of medicinal cannabis in Australia occurred in 2016 (Department of Health and Aged Care 2019). Soon after, access schemes were developed by the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA); however, medicinal cannabis remained an ‘unapproved drug’, with access pathways via the Special Access Scheme (SAS) and Authorised Prescribers (AP) or via clinical trials (Department of Health and Aged Care 2022). The result of the TGA access schemes resulted in multiple issues for Australian patients in gaining medicinal cannabis; these were highlighted in a 2020 Senate enquiry. Key problems identified included variations between states’ and territories’ schemes, limited availability of training for doctors and financial constraints for consumers (Parliament of Australia 2020).

In 2016, prior to regulatory changes made by the Australian Department of Health and Aged Care (2019), the Cannabis as Medicine Survey (CAMS‐16) was conducted in Australia to ascertain why patients were using cannabis for therapeutic effect (Lintzeris et al. 2018). Participants reported that cannabis relieved symptoms in relation to generalised anxiety, panic disorder and obsessive‐compulsive disorder, as well as for pain‐related disorders such as back and gynaecological pain. Two years after the 2016 CAMS survey, a repeat survey by Lintzeris et al. (2020) noted that despite consumers being able to access medicinal cannabis legally, only 2.4% of respondents reported legally obtaining medicinal cannabis. This low rate is related to ongoing difficulties with access (O’Brien 2019) and financial barriers (Parliament of Australia 2020).

Despite the best intentions of regulatory agencies, the implementation of medicinal cannabis in Australia was proving to be cumbersome. Gleeson (2020) analysed the legislative and regulatory changes in Australia from 2014 to 2018 and identified that the restrictive access pathway to medicinal cannabis left patients with two main pathways to access medicinal cannabis: SAS or AP pathways (Department of Health and Aged Care 2024). Nevertheless, the pathways were restrictive and required the support of doctors to authorise and prescribe medicinal cannabis.

Globally, the legal status of cannabis change is proving to be contentious. Legal issues were identified in countries such as the United States, around medicinal cannabis’ classification as a Schedule 1 controlled substance drug, which defined it as a drug of high potential for abuse and identified as having no acceptable use (Pacula and Smart 2017). Cannabis has been an illicit drug for more than 50 years for countries that signed the UN Single Convention which oversees narcotic drugs and classified cannabis alongside drugs such as cocaine and heroin (Hall et al. 2019; United Nations n.d.). Despite this illegality, it was estimated in 2016 that 192 million adults globally had used cannabis (Hall et al. 2019). Cannabis has a long history of being used as a medicine, and currently, 38 states in the United States allow use for medical purposes under strict qualifying conditions (Johnson and Colby 2023).

2. Background

Since medicinal cannabis has become available in Australia, an influx of interest in its perceived healthcare benefits has been noted, alongside increased media interest. Organisations within Australia have also been pivotal in advocating for Australian patients. United in Compassion (2014) is an Australian organisation, founded by Australian nurse Lucy Haslam, advocating for the use of medicinal cannabis after her son Dan used medicinal cannabis to help alleviate pain from bowel cancer. Legalisation of medicinal cannabis officially occurred in 2016; however, prior to this, there had been schemes developed to allow the use of medicinal cannabis. One of these schemes took place in 2014 and allowed registered individuals with a terminal illness to access cannabis for medical purposes (Parliament of Australia 2014). In 2015, Australia’s first clinical trial was also underway at Newcastle Hospital to test whether medicinal cannabis could improve the quality of life in terminally ill patients (Marchese 2015). Yet, the process for legal access to medicinal cannabis in Australia is reportedly cumbersome for patients as it is treated as a pharmaceutical and is an unapproved therapeutic good, as regulated by the Department of Health and Aged Care (2017). Additionally, access has been limited due to the current evidence‐based medicines approach and the question of whether there is sufficient evidence for medicinal cannabis’s use in mainstream healthcare.

Access to medicinal cannabis differed depending on geographical location. Tasmania, for example, had adopted the Medical Cannabis Controlled Access Scheme where specialist approval was required to obtain a script (Department of Health 2020), whereas all other states were prescribing medicinal cannabis under the SAS and AP schemes as governed by the TGA (Department of Health and Aged Care 2019). Applications to the TGA rose to 1596655 SAS‐B approvals since January 2020 (MacPhail et al. 2022).

In Australia, it is anticipated that nurses will be called upon to care for patients who use medicinal cannabis. Potential barriers to the delivery of safe and effective patient care need to be acknowledged. In Canada, a national needs assessment of nurse practitioners regarding legal cannabis for therapeutic purposes was conducted to identify knowledge and practice gaps to inform the development of future education resources. It was reported that the most significant knowledge gap was related to dosing and effective care plans for patients using medicinal cannabis for therapeutic purposes (Balneaves et al. 2018). Nurses in the United States cited limited research on medicinal cannabis as a medicine resulting in nurses caring for patients without evidence‐based resources (Russell 2019).

Oncology patients have been using medicinal cannabis for cancer palliation and seizure management, yet nurses in the United States have described being unable to answer basic questions about medicinal cannabis (Pirschel 2018). Studies of experiences of nurses’ experiences are limited and there is a dearth of literature about the role of nurses and medicinal cannabis. It is becoming increasingly important that Australian nurses are prepared in the clinical environment to care for patients using medicinal cannabis. Therefore, this study aims to describe Australian nurses’ experiences of caring for patients using medicinal cannabis. This study seeks to answer the following research question. What are the experiences of Australian nurses in caring for patients who use medicinal cannabis in Australian healthcare facilities?

3. Methods

3.1. Design

A qualitative approach was the most appropriate method to discover registered nurses’ experiences of caring for patients who use medicinal cannabis. A qualitative approach is appropriate when the researcher aims to discover multiple ways of understanding a phenomenon or experience (Streubert and Carpenter 2011). Braun and Clarke’s (2022) method of thematic analysis was selected to develop common themes across the dataset.

3.2. Recruitment

The target population included registered nurses caring for patients who use regulated medicinal cannabis that has been prescribed within Australian hospitals, aged care facilities and the community. Recruitment for this research was posted on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram. Purposive sampling as described by Low (2019) was used to gain insight from nurses who have had an experience with the research question. Recruitment continued until data saturation was reached, where no new information was gained (Merriam 2016). Participants’ characteristics are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Participants’ characteristics (n = 11).

| n | |

|---|---|

| Participant variable | |

| Male | 3 |

| Female | 8 |

| Country of birth | |

| Australia | 5 |

| Other | 6 |

| State and territory | |

| New South Wales | 5 |

| Queensland | 2 |

| Victoria | 1 |

| Western Australia | 1 |

| Tasmania | 0 |

| South Australia | 2 |

| Northern Territory | 0 |

| Clinical nursing roles | |

| Clinical Nurse Specialist | 1 |

| Clinical Nurse Consultant | 3 |

| Clinical Nurse Educator | 1 |

| Registered Nurses | 6 |

| Formal education about medicinal cannabis received in hospital | 2 |

| No education received about medicinal cannabis in hospital | 9 |

| Staff who have attended an external course on the use of medicinal cannabis | 3 |

3.3. Data Collection

Participants could choose to engage in interviews face to face on campus (n = 2) or online via Zoom (n = 9). A semistructured interview guide was used to ensure the same general area of information was collected from all participants. Eleven semistructured interviews lasting between 11 and 23 min each were conducted and recorded using Zoom by the first author, a female registered nurse with expertise in acute care nursing. Questions focused on range of reasons medicinal cannabis was being used by patients, nurses’ experiences with this, any personal or professional concerns regarding their role and the use of medicinal cannabis, and insights into the current legislative framework around medicinal cannabis. During interviews, participants were encouraged to openly discuss their experiences of caring for patients using medicinal cannabis. Interviews were recorded, transcribed verbatim by a professional transcription service and anonymised by the lead researcher.

3.4. Data Analysis

This study used Braun and Clarke (2022), a six‐step thematic analysis. Familiarisation with the data was achieved by reading and rereading the interview transcripts. As each participant’s transcript was reviewed by the first author, initial thoughts and ideas were written in a journal. Generating codes required the use of NVivo, which allowed data to be analysed across the entire dataset. Data coding simultaneously utilised an inductive and deductive approach (Holloway 2017), and emerging codes and themes were discussed and refined by the whole research team during regular research meetings.

Analysis of data required reviewing concrete data from participants’ responses and then interpreting the meaning behind the abstract concepts; Merriam (2016) noted that this allowed for a deeper understanding of the data. Codes were data driven and taken from direct quotes from the 11 participants as described by Fereday and Muir‐Cochrane (2006). Codes were initially assigned to construct possible categories (Merriam 2016). Each code was then collated and checked against the others back to the original dataset. Collectively, the analysis of the interviews yielded a number of subthemes and then potential themes. This iterative process of generating potential themes from a number of subthemes is listed in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Accessibility and management of medicinal cannabis in Australia.

| Themes | Subthemes |

|---|---|

| 1. Searching for predictable processes of regulation, access and use of medicinal cannabis | 1.1. Registered nurses’ understanding of medicinal cannabis scheduling |

| 1.2. Registered nurses’ perception of safety and efficacy of medicinal cannabis | |

| 1.3. Medicinal cannabis accessibility and use | |

| 2. One conundrum after another | 2.1. Registered nurses at the forefront |

| 2.2. Medicinal cannabis as a panacea | |

| 2.3. Stigma of medicinal cannabis | |

| 2.4. Registered nurses’ perception of doctors | |

| 3. There is a lot to learn | 3.1. Registered nurses seeking knowledge |

| 3.2. Availability of research evidence | |

| 3.3. Patients assuming that registered nurses have knowledge |

Potential themes were identified at this initial stage by the first author. These potential themes then underwent further analysis during research team meetings, and a thematic map was generated in NVivo that continued to undergo re‐evaluation. Ongoing analysis by the whole research team over multiple meetings resulted in the refinement of themes, and labels for each theme were identified.

3.5. Trustworthiness and Credibility

Trustworthiness was ensured through several means. The interviews were conducted by a skilled clinician and theoretical triangulation of the authors’ professional and research backgrounds. Four of the five authors reviewed all transcripts (NM, NW, PP and PL) all team members participated in coding and theme development and a clear audit trail for the analysis using NVivo as an analysis tool and Braun and Clarke’s (2022) six‐step approach to qualitative analysis.

3.6. Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from the Western Sydney University Research Ethics Committee (ID: 13189). Participants provided both written and verbal consent to being interviewed and to having their interview recorded, and there were no adverse events.

4. Results

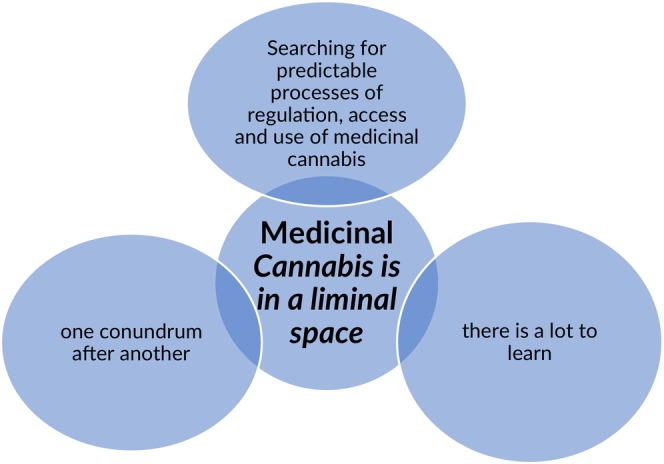

Three main themes were identified from the analysis (see Figure 1): (1) searching for predictable processes of regulation, access and use of medicinal cannabis, (2) one conundrum after another and (3) there is a lot to learn. In addition, an overarching construct was labelled medicinal Cannabis is in a liminal space.

FIGURE 1.

4.1. Searching for Predictable Processes of Regulation, Access and Use of Medicinal Cannabis

Participants described the availability of medicinal cannabis to patients, some of the regulations governing the administration of medicinal cannabis and the implications for patient safety. Participants discussed medicinal cannabis as being available to patients who qualified for it and could afford it. Participants also reported the use of cannabis for medicinal purposes acquired by illegal means by patients to whom medicinal cannabis was otherwise unavailable.

Access to medicinal cannabis is provided by prescription from a physician for patients who qualify to receive it. However, according to some participants, acquiring a prescription from a General Practitioner (GP) or medical specialist can be difficult for patients. ‘They go to the GP, and the GP says, Oh, I cannot prescribe it. Talk to your palliative doctor, and of course, the palliative doctors are saying, no, we are not. We are not prescribing it. So, they do not know where to go’ (Phoebe, community palliative care nurse).

Furthermore, participants described difficulty in finding physicians who were willing to prescribe medicinal cannabis. ‘Everyone is passing it back around; I cannot seem to pin anyone down. I would have thought of all people that palliative doctors might be the ones that would have been best placed to be involved with it’ (Phoebe, community palliative care nurse). Although medicinal cannabis is ostensibly available to patients who would benefit from it, gaining access to the drug was challenging for participants in this study and, reportedly, for their patients.

Another participant reported barrier to access to medicinal cannabis for patients is the financial cost. ‘[Patients] say it is expensive. They are paying something like $300’ (Sandra, community palliative care nurse). However, one participant viewed the financial cost of medicinal cannabis as being beneficial because it had the effect of restricting access for patients. ‘Apparently, patients are saying that it is expensive and maybe it is a good thing. Because it is expensive at the moment because can you imagine if it is cheaper then everybody else would be on it?’ (Felicity, chronic pain nurse).

According to participants, requests for access to medicinal cannabis were often initiated by patients who had exhausted other options for pain relief and had, in some cases, searched the internet for possible alternative pain relief methods. ‘She has tried everything pre cannabis, and she was left with no other options but to try it, and that is how she went online preadmission, and looked at other ways of pain medications, and this is how she came across the medicinal cannabis’ (Bill, aged care nurse).

The legalisation of medicinal cannabis in Australia raised some questions for registered nurses. Firstly, nurses needed to know how drugs were scheduled as this provides guidance for the safe administration of any medication. ‘The pharmacy would review it, and we can see that this person, takes [Tetrahydrocannabinol] THC and [Cannabidiol] CBD’ (Kirrien, palliative care clinical nurse educator). Secondly, participants’ perception of the safety of medicinal cannabis was also discussed in terms of dosage and interactions with other medications. ‘It just means for some patients, you just have to do some further monitoring of some levels in their blood, concerning certain medications’ (Toni, palliative care clinical nurse consultant).

Participants’ knowledge of medicinal cannabis regulation varied. Medicinal cannabis was introduced to hospitals as a Schedule 8 medication. Some participants were aware of this. ‘So [medicinal cannabis] is a Schedule 8, so we need a double signature each time, and then we just order another bottle’ (Matthew, mental health nurse). Some participants were unsure of medicinal cannabis’s scheduling. ‘When [patient] was first admitted… I was like, well, hang on, is it a schedule eight, is it a schedule four? Is she able to self‐administer, or do we have to?’ (Bill, aged care nurse). Some knew of the differences in scheduling but were critical of it. ‘I personally think that making cannabis or particularly the [Tetrahydrocannabinol] THC an [Schedule 8] medication and making [Cannabidiol] CBD an [Schedule 4] is outrageous as it is neither a Schedule 8 or Schedule 4 medication, it is a plant‐based medicine and should be treat as complimentary medicine’ (Toni, palliative care CNC). Scheduling is a tool designed to enhance patient safety by regulating accessibility to a drug. In circumstances such as these examples, uncertainty or apparently conflicting scheduling have potentially adverse implications for patient safety.

Participants discussed the safety of medicinal cannabis in terms of interaction with other drugs, dosage and management of adverse effects. Some participants, for example, perceived medicinal cannabis as a safer method of providing pain relief than administering opioids. ‘We had a number of opioid toxicities. … they are absolutely awful, and they can lead to death. I think cannabis is much safer’ (Toni, palliative care nurse). Others expressed concern about potential adverse effects related to the dosage of medicinal cannabis. ‘We need to be really careful because it is so concentrated, and people react to cannabis oil differently’ (Julie, spinal care nurse).

According to participants, the provision of medicinal cannabis in Australia presented practical challenges for both patients and nurses. Availability did not always mean accessibility, and regulation did not always guarantee safety from the nurses’ perspective.

4.2. One Conundrum After Another

The rapid introduction of medicinal cannabis into the Australian healthcare system has led to mystification, misunderstanding and misapprehension among patients and healthcare providers. Patients have questioned registered nurses about the use of medicinal cannabis without sufficient availability of information or practical guidelines. Participants expressed concern over extreme positions—on the one hand, medicinal cannabis is a panacea for curing all conditions, on the other, that medicinal cannabis is a moral evil that should be avoided, threatening to undermine the effective use of medicinal cannabis.

Participants discussed being at the forefront of patient clinical care and how they perceived the introduction of medicinal cannabis into the healthcare environment to be haphazard. Participants reported that patients had asked them questions about the possible use of medicinal cannabis, for example, during education sessions for pain management. ‘We had many questions during those sessions about medicinal cannabis, and they would be able to get it from us’ (Melissa, chronic pain nurse). Participants reported that patients erroneously assumed that nurses could provide medicinal cannabis access. For example, Melissa stated, ‘One of the reasons why a lot of them were referred to us, they said, was to get access to medicinal cannabis’. Participants reported that they often did not have the knowledge required to answer patients’ questions about medicinal cannabis confidently.

Participants also reported variability in the knowledge about medicinal cannabis possessed by their colleagues even when medicinal cannabis was in use within the hospital. For example, Julie related that:

Medicinal cannabis is relatively new to [some nurses] because not all the wards [in our hospital] use this. Furthermore, when we checked the drugs and other staff from different wards came to us to ask for some other medication from the [medication system], they saw us, and they were like, what is that? When we explained to them, they were curious, and they were like, oh, we did not know that we already have this in the hospital.

Participants reported the polarising effect of using medicinal cannabis among various social groups. On the one hand, Felicity suggested that ‘the community’ saw medicinal cannabis as a solution to all health ailments: ‘Some people swear by [medicinal cannabis] because their friends have convinced them that it works for them, and they think it is a magical thing. It is this whole medicinal cannabis panacea that it solves everyone’s problems’. On the other hand, opposition to the use of medicinal cannabis is reportedly related to the stigma associated with illicit drug use. For example, Bill reported a conversation with another nurse about using medicinal cannabis and stated, ‘There was a registered nurse who, she was like, Oh, I am not for it because it is marijuana’. Phoebe, another participant, also expressed concern over this and stated, ‘I think it has got bad connotations as cannabis has previously been used illicitly’. Polarising opinions about introducing new medicinal medications can adversely affect the uptake of that medicine and its safe and effective use.

4.3. There is a Lot to Learn

Participants described a need for knowledge about medicinal cannabis’s safe and effective use. At a macrolevel, participants perceived a need for more availability of high‐quality research evidence to support their practice. This meant that, at the personal level, participants had to seek opportunities to educate themselves about medicinal cannabis for the benefit of patients against a background of what they perceived to be limited institutional support. At the microlevel, participants perceived that their patients assumed that they had knowledge about how the use of medicinal cannabis applied in their circumstances when they did not necessarily possess that knowledge.

None of the participants described searching for research evidence in support of the use of medicinal cannabis for themselves. Instead, they derived that there is a lack of credible research evidence in favour of using medicinal cannabis from other health professionals. For example, one participant spoke with the pharmacists within their healthcare facility about research into medicinal cannabis. She was reportedly told that ‘The research that’s being done is mainly on children who have had seizures. You have probably seen that on 60 min or so on, but not a lot of research on the palliative side of things’. Phoebe said the pharmacist commented, ‘Look, they are just applying for licenses to grow it, and it is still a long way off’. It was conveyed to participants that this treatment may be useful, but not for all conditions.

When participants described seeking knowledge about the use of medicinal cannabis, they described seeking ‘training’ or instruction from other people. For instance, in the absence of any training provided by her institution, Kirrien said, in the absence of any training, ‘We have got in touch with [educational company] to see if we can arrange some education sessions’. Participants who wanted education to be more proactive rather than reactive expressed frustration. For example, Julie said, ‘You know what, the thing is they will not do [ward] education until one of the patients using it [medicinal cannabis]. I think it is best to just educate [nurses] any way that this already exists and that it is working in some patients. If more nurses received education prior to caring for patients that are using medicinal cannabis it would not be such a surprise’. Although education was needed, the education received was not always viewed favourably. For example, Toni stated, ‘I have not been happy with the quality of that education and … I have yet to see someone in my opinion, who has got the level of experience that I require when I go and get that information’.

Patients often make a legitimate assumption that registered nurses know about their illnesses, conditions and care options. This applies to treatment with medicinal cannabis as it does in many other clinical contexts. Participants discussed how this assumption was expressed in three ways. Firstly, they described how some patients asked for information about medicinal cannabis directly. Tracy said, ‘Most of the time, it is coming from the patient’s side. Can I try this?’ Secondly, family members reportedly asked participants about the use of medicinal cannabis for the patient. For example, Phoebe said, ‘So his wife, as part of advocating for him, I suppose asked about where we could get medicinal cannabis from … We are getting this a lot’. Critically unwell patients reportedly relied on their family members to advocate for them even when they were unsure how to execute the patient’s request. Thirdly, some participants said their colleagues knew they could share information about medicinal cannabis with the patients. For instance, Toni stated, ‘So anytime someone came in that had medicinal cannabis or wanted to talk about it, they would tell me. And then I would go and talk to patients’. As most participants described their educational confidence in medicinal cannabis’s use as low, this was a rare occurrence.

5. Discussion

This study has, for the first time, shone a light on the experiences of Australian nurses who have cared for patients who use medicinal cannabis across multiple contexts. The findings highlight a number of conundrums nurses face when caring for patients who use medicinal cannabis for therapeutic reasons. Nurses described being at the forefront of the issues surrounding medicinal cannabis’s use, and this presented three overarching and critical issues: These are patients’ reliance on nurses to fill their knowledge gap about medicinal cannabis, tensions related to the illicit use of medicinal cannabis and doctors’ reluctance to prescribe medicinal cannabis. Most importantly, for the nursing profession, the likelihood that all nurses will care for patients who use medicinal cannabis at some time during their careers has increased and will continue to do so. Yet, these nurses’ clinical preparedness still needs to be fully appreciated and understood.

Patients relied on nurses to answer questions about medicinal cannabis and perceived that nurses could provide comprehensive answers about its therapeutic use. Nurses being experts in the eyes of patients is not an unusual phenomenon. Indeed, nurses working within speciality areas are expected to have expert knowledge (Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia 2021). Nevertheless, nurses were only sometimes confident in supporting patients using medicinal cannabis and often could not answer patients’ questions about medicinal cannabis. The nurse’s role is evolving, and further support is required for confident responses from nurses.

Nurses have been calling for more information about medicinal cannabis to better support patients. The likelihood of patients using medicinal cannabis has been increasing the need for nurses to provide knowledge and effective care. Nurse practitioners in Canada have identified a lack of knowledge as being a barrier to discussing medicinal cannabis with patients (Balneaves et al. 2018). Difficulty answering patients’ questions could have the dual adverse effects of eroding a nurse’s self‐confidence and eroding patients’ confidence in their nurses’ capabilities. Either way, a lack of knowledge resulting in a lack of confidence could have adverse consequences for nurse–patient relationships which might jeopardise the quality of a patient’s care. Open communication is vitally important for patients to use medicinal cannabis successfully. Nurses have an opportunity to engage in meaningful discussions about medicinal cannabis with their patients, however, they are currently hampered by their lack of knowledge of the use of medicinal cannabis. Carlini, Garrett, and Carter (2017) stated that patients might hesitate to talk to nurses about medicinal cannabis’s safe and effective use due to nurses’ perceived reluctance to discuss medicinal cannabis openly. Patients may perceive that the nurse does not know what they are talking about or be complacent in their attitudes towards patients using medicinal cannabis as a medical modality. Participants in the current study discussed wanting to support patients using medicinal cannabis but needed the background knowledge to feel comfortable providing adequate responses. Consequently, patients would seek information about medicinal cannabis from sources other than their nurse and might receive incorrect information, which undermines medicinal cannabis’s safe and effective use.

Furthermore, Carlini, Garrett, and Carter (2017) reported that nurses in Washington State, USA, sought information about medicinal cannabis from non–peer‐reviewed sources such as news and media articles, followed by information from patients and other doctors. The potential negative impact of seeking information from nonscientific sources is substantial. Nurses who participated in the current study were more active in supporting patients using medicinal cannabis and providing correct information. However, Australia’s current and inadequate systems have been causing barriers preventing nurses from providing supportive information. The absence of clinical guidelines due to many medicinal cannabis products not having undergone clinical trials has resulted in a reduction in clinical guidance for Australian nurses.

Most Australian nurses have been educated in a system where cannabis is considered illegal and not for medical use. Thus, it is challenging to reconcile the illegal use of cannabis and the use of medicinal cannabis for therapeutic purposes. This challenge is exacerbated when nurses care for patients who use medicinal cannabis illegally while admitted to Australian healthcare facilities. This is a critical issue for professional nursing practice and nursing ethics, particularly concerning the nurse’s role in promoting better patient outcomes, because it imposes a choice on nurses to either ‘turn a blind eye’ to the use of illicit cannabis in the belief that it has some therapeutic value for a particular patient, or to prohibit the use of illegal cannabis and risk compromising the development of an effective therapeutic relationship. A recent Australian study by Lintzeris et al. (2020) of patients who use medicinal cannabis reported that out of 1388 participants who use medicinal cannabis, only 37 (2.7%) had accessed medicinal cannabis legally. At present, nurses are far more likely to care for patients using medicinal cannabis illegally than patients accessing medicinal cannabis legitimately. The choice of whether to ‘turn a blind eye’ is, therefore, likely to be made by nurses frequently, even daily.

Participants in this study described how they had cared for patients using medicinal cannabis illegally. Nurses chose to let the patient use the medicinal cannabis they had brought into the hospital without reporting to the medical team. This also occurred with nurses working in the United States, where some hospice workers discussed turning a blind eye to the illegal use of smoked marijuana if they believed that the patient had received some symptom control (Luba et al. 2018). In the current study, nurses were compassionate and understanding towards patients who used illicitly obtained cannabis if they believed it would bring relief. Nonetheless, nurses did express concern about patients storing cannabis in their bedside drawers due to inadequate security measures, which could potentially lead to theft. A US survey also discussed a similar issue by raising concerns over storing or administering illegal medicinal cannabis in the inpatient setting as there was potential for recreational use or theft by family members (Costantino et al. 2019). Nurses in similar situations also must decide where they stand morally on using cannabis for recreational purposes. The use of illegal medicinal cannabis has several potentially adverse consequences. Nurses might be vulnerable to some form of legal sanction based on their knowledge that patients are consuming illegal substances, and patients are likely to be exposed to cannabis of varying quality that they consume in ways that may be harmful to their health. How Australian nurses will continue to support patients to use medicinal cannabis if they are consuming illegal medicinal cannabis is yet to be explored in any detail. Regardless of how patients choose to access and use medicinal cannabis, nurses still want to support them to use medicinal cannabis and require support from doctors. To date, three articles in Australia have reviewed the position of Australian doctors and pharmacists regarding medicinal cannabis for therapeutic use (Irvine 2006; Isaac, Saini, and Chaar 2016; Karanges et al. 2018). In the most recent article, Karanges et al. (2018) surveyed the knowledge and attitudes of Australian GPs. In this survey, GPs were supportive of medicinal cannabis where there was a more robust evidence base, such as in conditions such as multiple sclerosis and chemo‐induced vomiting and nausea, and less support for conditions such as chronic noncancer pain. GPs were concerned about the inappropriate use of medicinal cannabis associated with prescription opioids. However, in Washington, doctors were beginning to understand that medicinal cannabis may be a safer option than opioids (Carlini, Garrett, and Carter 2017). Since Australian legislative changes in 2016, doctors have reportedly displayed uncertainty in prescribing medicinal cannabis for patients. Karanges et al. (2018) describe limited evidence of medicinal cannabis’s safety and efficacy has resulted in GP caution. A Senate inquiry in 2020 that reviewed barriers to accessing medicinal cannabis in Australia found that doctors did not have the confidence to discuss medicinal cannabis with patients as they lacked general knowledge (Parliament of Australia 2020). Additionally, many GPs doubted medicinal cannabis’s efficacy and safety and believed that medicinal cannabis should only be used as a ‘last resort’. Australian GPs’ reluctance to prescribe medicinal cannabis has reportedly included inadequate knowledge of medicinal cannabis, resulting in a reluctance to discuss it with their patient (Karanges et al. 2018). Patients might ask nurses questions about the use of medicinal cannabis for their condition if they are unable to discuss the topic with a medical practitioner. However, without adequate education nurses might consider themselves ill equipped to meet patients’ needs. Nurses will need to consider how to support patients in utilising medicinal cannabis as a medicine.

Nurses are at the forefront of patient care and are currently in a position where they can begin to provide support for patients. Kurtzman et al.’s (2022) recent study of American nurses identified the need for the nursing profession to become more involved. However, to do this, education is needed and nurses should advocate for patient use. Luba et al. (2018), in another US study examining the attitudes and practices of palliative care providers, found that although some palliative care providers endorsed the use of medicinal cannabis in palliative care, they do not then prescribe medicinal cannabis for their patients and were less likely to prescribe it if the patients are elderly. This indicates that doctors are still reluctant to adopt medicinal cannabis as a treatment or care option for palliative care patients. There appears to be an inconsistency between nurses’ expectations of doctors to discuss medicinal cannabis’s use with patients and doctors’ capacity to do so. Given that doctors and nurses are similarly disadvantaged in terms of preparation, knowledge and understanding of medicinal cannabis, nurses might have to be proactive themselves and lead a push to increase medicinal cannabis’s knowledge and understanding for all health professionals.

5.1. Strengths and Limitations

This study has several strengths, the first being that nurses from five states in Australia volunteered to participate in this research study. This strengthened the study as nurses from the different states were governed by differences in health systems and guided by variations in regulations, allowing for nurses’ range of experiences in these states. No nurses from Tasmania participated in this study; this would have added depth to the study as Tasmanian patients only have access to medicinal cannabis through specialist approval, a unique situation among all Australian states. Additionally, the voluntary nature of the recruitment strategy resulted in nurses interested in the phenomenon being studied. Limitations within qualitative research rely on the participants involved. This may result in skewed views either in favour or vehemently against medicinal cannabis in the healthcare sector.

Other limitations included only two face‐to‐face interviews, while the remaining nine were conducted via the telephone due to COVID‐19. Nurses may have felt more comfortable discussing their experiences of caring for patients using medicinal cannabis if they had a face‐to‐face interview. In total, 11 nurses took part in this study, which may not represent the population. The author believes this does not distract from this study’s usefulness in showcasing the experience of nurses caring for patients who use medicinal cannabis and the barriers experienced by nurses in providing holistic care.

6. Conclusion

The rapid increase in patients using medicinal cannabis in Australia has resulted in patient care and professional care issues. This research has identified obstacles for patients in accessing and using medicinal cannabis and its impact on nurses rather than caring for patients who choose to use medicinal cannabis for therapeutic purposes. Nurses have overcome challenges by supporting patients who want to use medicinal cannabis for medicinal purposes. Nurses have an opportunity in Australia to voice their opinions and assist with developing policies and procedures. This research has allowed participants to express their perceptions and views on medicinal cannabis’s use within Australian hospitals, aged care facilities and communities.

7. Relevance to Clinical Practice

Findings from research can inform future practice by identifying current clinical practice issues as patients’ clinical care is guided by the best available evidence (Curtis et al. 2017). Medicinal cannabis in the clinical field is in its infancy, and currently, there is a lack of understanding of medicinal cannabis as a medicine. Nurses are at the forefront of patient care and have an opportunity to support patients in their choice to use medicinal cannabis for symptom management. Back pain is the most common reason patients are accessing medicinal cannabis in Australia, followed by arthritic pain, nerve pain and fibromyalgia (Lintzeris et al. 2020), and research is currently focused on medicinal cannabis as a part of cancer management (Hewa‐Gamage et al. 2019). Training programmes could be made available for nurses in areas other than oncology but based on the experiences of nurses working in oncology to bridge the knowledge gap and allow for holistic care for patients that incorporate medicinal cannabis within. In Australia, the palliative care field has already registered its interest in medicinal cannabis as an antiemetic in terminally ill patients by conducting a review for Australian nurses (Chan et al. 2017). Thus, training programmes could initially focus on palliative care nurses. Education targeted at palliative care nurses could occur online and focus on current issues identified by this study. Training programmes for nurses were developed in Washington, USA, in 2013 so that nurses and other healthcare providers could be aware of medicinal cannabis’s scientific basis alongside possible clinical implications and legal ramifications for patients who use medicinal cannabis for chronic pain (Carlini, Garrett, and Carter 2017).

Including education for nurses in Australia would allow nurses to improve their confidence and competence when caring for patients who use medicinal cannabis incorporated into their treatment plan.

The findings of this research indicate that while advocating for patients to access and utilise medicinal cannabis as a treatment option, the knowledge and understanding of medicinal cannabis as medicine is low. Many reported the requirement for education to increase confidence levels when discussing medicinal cannabis with patients. This analysis supports the nurse’s role and highlights the future importance of providing meaningful education for all nurses at both an undergraduate and preregistration level.

Author Contributions

Nicole McIntosh: conception design of work, data collection and analysis, drafting and revision of manuscript, leadership of the research team. Nathan J. Wilson: supervision, conception of design and work, review and editing. Petra Povalej: conception of design and work, review and editing. Leanne Hunt: critical revision of manuscript, review and editing. Peter Lewis: methodology, supervision, conception of design and work, review and editing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

The researchers would like to express their gratitude to those registered nurses who agreed to participate in this research. Open access publishing facilitated by Western Sydney University, as part of the Wiley ‐ Western Sydney University agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Data Availability Statement

Research data are not shared.

References

- Balneaves, L. G. , Alraja A., Ziemianski D., McCuaig F., and Ware M.. 2018. “A National Needs Assessment of Canadian Nurse Practitioners Regarding Cannabis for Therapeutic Purposes.” Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research 3, no. 1: 66–73. 10.1089/can.2018.0002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V. , and Clarke V.. 2022. “Conceptual and Design Thinking for Thematic Analysis.” Qualitative Psychology 9, no. 1: 3. 10.1037/qup0000196. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carlini, B. H. , Garrett S. B., and Carter G. T.. 2017. “Medicinal Cannabis: A Survey Among Health Care Providers in Washington State.” American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Medicine 34, no. 1: 85–91. 10.1177/1049909115604669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan, A. , Molloy L. J., Pertile J., and Inglesias M.. 2017. “A Review for Australian Nurses: Cannabis Use for Anti‐Emesis Among Terminally Ill Patients in Australia.” Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing 34, no. 3: 43–47. 10.37464/2017.343.1524. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Costantino, R. C. , Felten N., Todd M., et al. 2019. “A Survey of Hospice Professionals Regarding Medical Cannabis Practices.” Journal of Palliative Medicine 22, no. 10: 1208–1212. 10.1089/jpm.2018.0535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis, K. , Fry M., Shaban R. Z., and Considine J.. 2017. “Translating Research Findings to Clinical Nursing Practice.” Journal of Clinical Nursing 26, no. 5–6: 862–872. 10.1111/jocn.13586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health . 2020. “Medicinal Cannabis.” Accessed May 17, 2024. https://www.health.tas.gov.au/health‐topics/medicines‐and‐poisons‐regulation/medicinal‐cannabis/regulatory‐framework‐medicinal‐cannabis.

- Department of Health and Aged Care . 2019. “Introduction to Medicinal Cannabis Regulation in Australia.” Accessed May 5, 2024. https://www.tga.gov.au/blogs/tga‐topics/introduction‐medicinal‐cannabis‐regulation‐australia.

- Department of Health and Aged Care . 2017. “Medicinal Cannabis Products: Patient Information.” https://www.tga.gov.au/access‐medicinal‐cannabis‐products.

- Department of Health and Aged Care . 2019. “Introduction to Medicinal Cannabis Regulation in Australia.” https://www.tga.gov.au/news/blog/introduction‐medicinal‐cannabis‐regulation‐australia.

- Department of Health and Aged Care . 2022. “Medicinal Cannabis: Access Pathways and Patient Access Data.” https://www.tga.gov.au/products/unapproved‐therapeutic‐goods/medicinal‐cannabis‐hub/medicinal‐cannabis‐access‐pathways‐and‐patient‐access‐data.

- Department of Health and Aged Care . 2024. “Medicinal Cannabis: Access Pathways and Usage Data.” https://www.tga.gov.au/products/unapproved‐therapeutic‐goods/medicinal‐cannabis‐hub/medicinal‐cannabis‐access‐pathways‐and‐usage‐data.

- Fereday, J. , and Muir‐Cochrane E.. 2006. “Demonstrating Rigor Using Thematic Analysis: A Hybrid Approach of Inductive and Deductive Coding and Theme Development.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 5, no. 1: 80–92. 10.1177/160940690600500107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gleeson, P. 2020. “The Challenge of Medicinal Cannabis to the Political Legitimacy of Therapeutic Goods Regulation in Australia.” Melbourne University Law Review 43, no. 2: 558–604. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, W. , Stjepanović D., Caulkins J., et al. 2019. “Public Health Implications of Legalising the Production and Sale of Cannabis for Medicinal and Recreational Use.” Lancet 394, no. 10208: 1580–1590. 10.1016/s0140-6736(19)31789-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewa‐Gamage, D. , Blaschke S., Drosdowsky A., Koproski T., Braun A., and Ellen S.. 2019. “A Cross‐Sectional Survey of Health professionals’ Attitudes Toward Medicinal Cannabis Use as Part of Cancer Management.” Journal of Law and Medicine 26, no. 4: 815–824. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holloway, I. 2017. Qualitative Research in Nursing and Healthcare. 4th ed. Hoboken: Wiley Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Irvine, G. 2006. “Rural Doctors’ Attitudes to and Knowledge of Medicinal Cannabis.” Journal of Law and Medicine 14, no. 1: 135–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaac, S. , Saini B., and Chaar B. B.. 2016. “The Role of Medicinal Cannabis in Clinical Therapy: Pharmacists’ Perspectives.” PLoS One 11, no. 5: e0155113. 10.1371/journal.pone.0155113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, J. K. , and Colby A.. 2023. “History of Cannabis Regulation and Medicinal Therapeutics: It’s Complicated.” Clinical Therapeutics 45, no. 6: 521–526. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2023.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karanges, E. A. , Suraev A., Elias N., Manocha R., and McGregor I. S.. 2018. “Knowledge and Attitudes of Australian General Practitioners Towards Medicinal Cannabis: A Cross‐Sectional Survey.” British Medical Journal Open 8, no. 7: e022101. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtzman, E. T. , Greene J., Begley R., and Drenkard K. N.. 2022. ““We Want What’s Best for Patients.” Nurse Leaders’ Attitudes About Medical Cannabis: A Qualitative Study.” International Journal of Nursing Studies Advances 4: 100065. 10.1016/j.ijnsa.2022.100065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lintzeris, N. , Driels J., Elias N., Arnold J. C., McGregor I. S., and Allsop D. J.. 2018. “Medicinal Cannabis in Australia, 2016: The Cannabis as Medicine Survey (CAMS‐16).” Medical Journal of Australia 209, no. 5: 1–6. 10.5694/mja17.01247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lintzeris, N. , Mills L., Suraev A., et al. 2020. “Medical Cannabis Use in the Australian Community Following Introduction of Legal Access: The 2018–2019 Online Cross‐Sectional Cannabis as Medicine Survey (CAMS‐18).” Harm Reduction Journal 17, no. 1: 1–12. 10.1186/s12954-020-00377-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low, J. 2019. Unstructured and Semi–Structured Interviews in Health Research. Researching Health: Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed methods, 123–141. London, UK: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Luba, R. , Earleywine M., Farmer S., and Slavin M.. 2018. “Cannabis in End‐of‐Life Care: Examining Attitudes and Practices of Palliative Care Providers.” Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 50, no. 4: 348–354. 10.1080/02791072.2018.1462543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacPhail, S. L. , Bedoya‐Pérez M. A., Cohen R., Kotsirilos V., McGregor I. S., and Cairns E. A.. 2022. “Medicinal Cannabis Prescribing in Australia: An Analysis of Trends Over the First Five Years.” Frontiers in Pharmacology 13: 885655. 10.3389/fphar.2022.885655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchese, D. 2015. “Australia’s First Medical Cannabis Study Announced at Newcastle Hospital: The NSW Government Has Announced the First Medical Cannabis Trial for Terminally Ill Adults Will Be Carried Out at a Newcastle Hospital.” ABC Premium News.

- Merriam, S. B. 2016. “Dealing With Validity, Reliability, and Ethics.” In Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation, edited by Tisdell E. J., 4th ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey‐Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia . 2021. “Professional Standards.” https://www.nursingmidwiferyboard.gov.au/Codes‐Guidelines‐Statements/Professional‐standards.aspx.

- O’Brien, K. 2019. “Medicinal Cannabis: Issues of Evidence.” European Journal of Integrative Medicine 28: 114–120. 10.1016/j.eujim.2019.05.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pacula, R. L. , and Smart R.. 2017. “Medical Marijuana and Marijuana Legalization.” Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 13: 397–419. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032816-045128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parliament of Australia . 2014. “Regulator of Medicinal Cannabis Bill 2014.” https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Bills_LEGislation/Bills_Search_Results/Result?bId=s987.

- Parliament of Australia . 2020. “Current Barriers to Patient Access to Medicinal Cannabis in Australia.” https://www.aph.gov.au/parliamentary_business/committees/senate/community_affairs/medicinalcannabis/report.

- Pirschel, C. 2018. “Understanding Medicinal Cannabis in Cancer Care.” Oncology Nursing Society 33, no. 1: 18–22. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, K. A. 2019. “Caring for Patients Using Medical Marijuana.” Journal of Nursing Regulation 10, no. 3: 47–61. 10.1016/s2155-8256(19)30148-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair, J. , Adams C., Thurgood G., Davidson M., Armour M., and Sarris J.. 2020. “Cannabidiol (CBD) Oil Rehashing the Research, Roles and Regulations in Australia.” Australian Journal of Herbal and Naturopathic Medicine 32, no. 2: 54–60. 10.33235/ajhnm.32.2.54-60. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Streubert, H. J. , and Carpenter D. R.. 2011. Qualitative Research in Nursing: Advancing Humanistic Imperative. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott‐Williams & Willkins. [Google Scholar]

- United in Compassion . 2014. https://unitedincompassion.com.au/.

- United Nations . 2020. “Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, 1961.” https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/treaties/single‐convention.html?ref=menuside.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Research data are not shared.