Learn more: PMC Disclaimer | PMC Copyright Notice

. 2024 Oct 30;2024:5772961. doi: 10.1155/2024/5772961

Abstract

Tea is a rich source of phytochemicals; their composition in tea extracts varies depending on the cultivar, climate, production region, and processing and handling processes. The method of extraction plays a crucial role in determining the biological effects of the bioactive compounds in tea leaves. However, reports on the catechin profiles and antioxidant activities of the extracts obtained from leaves at different stages of maturity are limited. Here, we aimed to evaluate the effect of ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE) and different drying methods, freeze drying (FD) and spray drying (SD), on the composition of bioactive compounds, phenolic composition, and antioxidant activity of extracts obtained from different part of leaves, top (TT), middle (ML), and mature (MT), of Assam tea cultivar (Camellia sinensis var. assamica) cultivated in Thailand (Thai Assam tea). High-performance liquid chromatography analysis showed that the extracts obtained by UAE with FD from TT leaves (UAEFD-TT) had the highest catechins (341.38 ± 0.11 mg/g extract) and caffeine (93.20 ± 0.36 mg CF/g extract) contents compared with those extracted from ML and MT using the same method as well those obtained by SD. The total phenolic and total flavonoid contents were the highest in UAEFD-TT extracts (456.78 ± 4.31 mg GAE/g extract and 333.98 ± 0.83 mg QE/g extract, respectively). In addition, UAEFD-TT exhibited the highest antioxidant activity; the IC50 values obtained by 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) and 2,2′-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS) assays were 1.31 ± 0.02 and 7.51 ± 0.03 μg/mL, respectively. In the ferric-reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) assay, the UAEFD-TT extract demonstrated the highest antioxidant activity (324.54 ± 3.33 μM FeSO4/mg extract). These results suggest that extraction from TT using UAE followed by FD produced the highest amount of antioxidant compounds in Thai Assam tea extracts.

1. Introduction

Tea, made by steeping processed leaves, buds, or twigs of the tea plant (Camellia sinensis) in hot water, is a widely consumed beverage globally. Tea is known for its various flavors, aromas, and health benefits and is consumed in several different forms, such as green, black, or oolong tea. Green tea leaves predominantly contain the catechin epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) (40%–69%), followed by epigallocatechin (EGC) (12%–23%), epicatechin gallate (ECG) (13%–21%), and epicatechin (EC) (5%–9%) [1–3]. Nonetheless, these ratios may differ depending on factors such as environmental conditions, type of tea, and agricultural methods such as harvest timing and the age of the leaves [4, 5]. In addition, younger leaves contained greater amounts of EGCG and ECG when compared to older leaves, while the mature (MT) leaves exhibited higher levels of EGC and EC. This suggests that the catechin profiles in green tea extracts (GTEs) can differ based on the origin, age of the tea leaves, and the method of extraction employed, which may influence their antioxidant properties [6, 7]. Tea polyphenols, commonly known as catechins, are unique constituents of tea and account for 30%–42% of the soluble ingredients in tea. Green tea has been reported to exhibit numerous health benefits [8–10]. The antioxidant activities of catechins are closely related to their structure. For instance, hydroxyl groups at Positions 5 and 7 of the A-ring, an ortho-3′4′-dihydroxyl group (catechol) or 3′4′5′-trihydroxyl group (pyrogallol) in the B-ring, and a gallate group located at Position 3 of the C-ring contribute to the antioxidant properties of polyphenolic compounds [11]. Preclinical and human studies have revealed the antioxidant, antimicrobial [12–14], antidiabetes [14], [15–17], anti-β-amyloid [18], anticancer [14, 19], anti-inflammation [20, 21], antiallergy [22, 23], and antiviral effects of catechins [24–26]. Despite these health benefits, catechins are also the major contributors to the astringency and bitterness of green tea infusions [15, 27]. These properties of the catechins are influenced by several factors, such as molecular size, chemical structure, and interactions with other compounds. For instance, catechins have a large molecular size and comprise many hydrogen bonds, which affects their bioavailability. Furthermore, the varied behaviors of the catechins, including their bioactivity and intermolecular interactions, are attributed to the differences in their steric configuration and molecular structure of catechins [28]. In addition, the extraction plays a crucial role in determining the biological effects of the bioactive compounds in tea leaves.

Different methods such as solvent extraction, mechanical expelling, supercritical fluid extraction, microwave-assisted extraction, and ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE) are employed for the recovery of bioactive compounds in tea leaves. Among these methods, UAE is preferred over others owing to their potential limitations, such as the use of extra solvent in solvent extraction, low yield in mechanical expelling, large capital in supercritical fluid extraction, and the requirement of an aqueous phase in microwave-assisted extraction. Furthermore, high-temperature extraction often leads to the degradation of polyphenols as well as increased protein and pectin extraction, which interfere with the organoleptic quality of tea by cream formation. In contrast, the UAE has advantages such as reduced time and energy requirements, extraction at low temperatures, and retention of extract quality [29, 30]. In this process, the mechanical and thermal effects of high-frequency sound waves are used to disrupt cell tissues to release the bioactive compounds, which facilitate the efficient extraction of plant materials [31], including phenolic and flavonoid compounds [30, 32–35]. This method has gained popularity in various industries, particularly the food and pharmaceutical industries [36]. UAE is also widely used in tea leaf extraction and has been shown to increase polyphenol yield at a low temperature (65°C) compared with that at high temperature (85°C) [37–39].

The drying process significantly affects the quality of GTE, as it can impact the concentration of bioactive compounds and the overall quality of the extract. Two common methods used for drying GTE are spray drying (SD) and freeze drying (FD). Studies have demonstrated that SD is a widely used method for drying GTE due to its efficiency and cost-effectiveness [40–42]. While FD is particularly favored for its ability to retain the bioactive compounds [43–45] by preventing the thermal degradation of temperature-sensitive compounds [46] and preserving sensory attributes of the extract [47].

In Thailand, two major tea varieties, Assam tea (Camellia sinensis var. assamica) and Chinese tea (C. sinensis var. sinensis), are cultivated. Among them, Assam tea (hereinafter referred to as Thai Assam tea) is the major tea variety and is cultivated in a larger planting area than Chinese tea [48]. Thai Assam tea, particularly in its black tea form, is one of the most widely consumed beverages in Thailand. In addition, Thai Assam tea is used in northern Thailand to produce traditional fermented chewing snack products, such as Miang [49]. Studies have reported that Thai Assam tea exerts antioxidant [50–55], antimicrobial [51, 52], anti-inflammatory [52, 55], alpha-amylase [52], alpha-glucosidase [52], and anticancer [51, 56, 57] activities. However, reports on the catechin profiles and antioxidant activities of the extracts obtained from leaves at different stages of maturity are limited. Therefore, in this study, we aimed to determine the effects of UAE extraction followed by drying using different methods, such as FD and SD, on the catechin contents of the extracts obtained from the different ages of tea leaves: top (TT), middle (ML), and MT leaves using UAE. In addition, we assessed the antioxidant properties of all Thai Assam tea extracts.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection and Processing

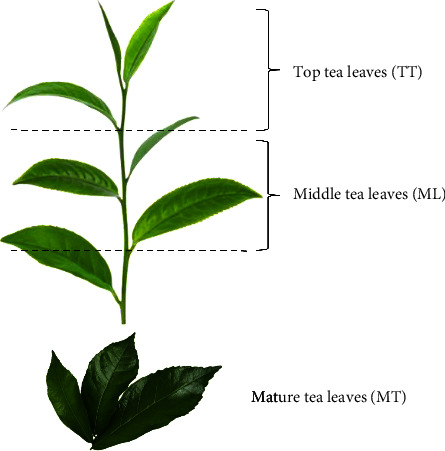

Thai Assam tea leaves were obtained from the Wawee tea plantation (Chiang Rai, Thailand) in 2023. The top leaves were carefully harvested, then withered and dried at 60°C for 120 min, reducing the moisture content to approximately 5%, This process followed a method similar to green tea production, which involves no oxidation and no fermentation. The leaves were placed in a sealed plastic bag and immediately transferred to the Tea and Coffee Institute’s Laboratory, Mae Fah Luang University (Chiang Rai, Thailand). The dried tea leaves were categorized into three age groups: TT, comprising the first and second leaves after the bud; ML, comprising the third to sixth leaves; and MT, comprising the seventh and older leaves (Figure 1). The samples from the three different ages were then ground separately into powder forms (particle size of approximately 150 μm) using a commercial laboratory blender homogenizer (51BL30, Waring Commercial, USA). All samples were placed in plastic bags and stored at ambient temperature until extraction.

Figure 1.

2.2. Preparation of Thai Assam Tea Extract

2.2.1. UAE

Approximately 100 g ground samples (TT, ML, and MT) were mixed with 50% ethanol (%v/v) at a fixed solid/liquid ratio of 1:20 (%w/v) [58]. The extraction was carried out in an ultrasonic water bath (Elmasonic S100; Elma Schmidbauer GmbH, Singen, Germany). The UAE was performed under the following conditions: 30°C and operated at 37 kHz frequency for 20 min [33]. The extracts were then filtered using a Whatman® No. 1 filter paper. Each filtrate was concentrated to dryness in a rotary evaporator (Heidolph Instruments GmbH & Co., Germany) at a controlled temperature (50°C) to obtain the final crude extracts, which were then stored at 4°C in a refrigerator until further use (Table S1).

2.2.2. SD and FD

SD was carried out using a spray dryer (Büchi, Flawil, Switzerland). A two-fluid nozzle with a capacitive diameter of 0.5 mm was used. The operating conditions were as follows: drying air inlet temperature, 200°C–350°C; atomization air volumetric flowrate, 400 L/h; feed volumetric flow rate, 3 mL/min; and drying air volumetric flow rate, 35–38 m3/h. The air outlet temperature (80°C) was measured for each extract, and the final extract was stored at −30°C in a refrigerator until further use (Table S1).

For FD, the crude extracts obtained in Section 2.1.1 were frozen at −40°C for 48 h and placed in a freeze dryer equipped with a capacitance manometer to monitor the condenser pressure for 48 h under vacuum (0.1–0.01 mmHg) until a constant moisture content was achieved. The chamber and ice condenser temperatures were set at −45°C to obtain the final extracts, which were then stored at −30°C in a refrigerator until further use (Table S1).

2.3. Determination of Contents of Catechin Derivatives and Caffeine (CF)

The final extracts (0.1 g) obtained in Section 2.2 (UAESD-TT, UAESD-ML, UAESD-MT, UAEFD-TT, UAEFD-ML, and UAEFD-MT) were dissolved in 100 mL stabilizing solution (10% acetonitrile with 500 μg/mL ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) and 500 μg/mL ascorbic acid) at a concentration of 1 mg/mL. The solution was then filtered through a 0.22 μm nylon membrane filter and used as the sample for HPLC analysis.

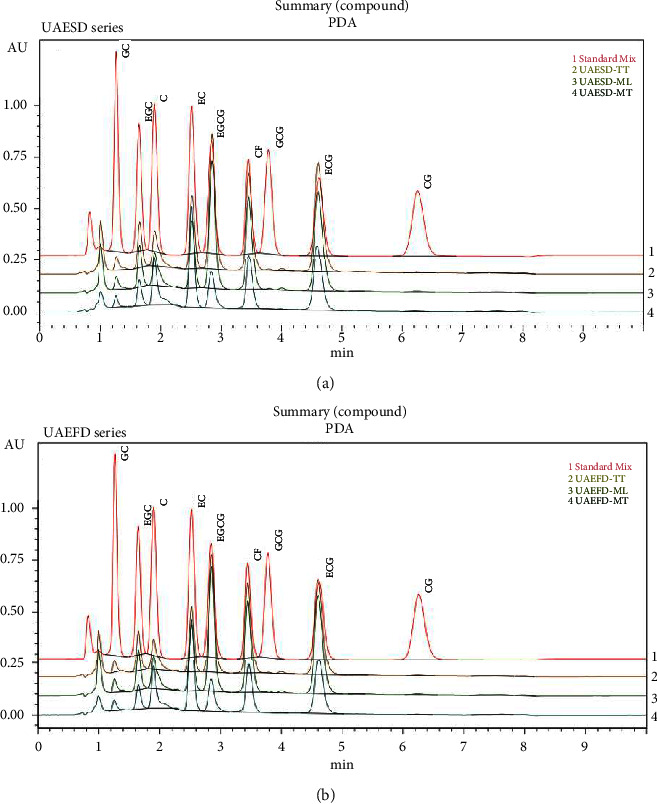

The contents of catechin derivatives and CF were quantified using HPLC, as described in a previous study [59]. HPLC was performed using a Nexera LC-40B xR system consisting of an autosampler (Shimadzu, Japan), a column oven (Shimadzu, Japan), and a photodiode array detector (Shimadzu, Japan). Liquid chromatography was performed using a Platinum C18-EPS column (53 × 7 mm, 3 μm) controlled at 35°C with isocratic elution at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The mobile phase comprised acetonitrile and 0.05% TFA at a ratio of 13:87 (v/v). The injection volume was 10 μL, and the total run time was 10 min. The measurement wavelength was set at 210 nm. The standard curve developed using catechin derivatives and CF purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (USA) was used to quantify their contents in the extracts. The retention times of the reference standards and the tea extracts containing various components were as follows: gallocatechin, GC 1.271 min; EGC 1.668 min; catechin, C 1.937 min; EC 2.563 min; EGCG 2.828 min; CF 3.465 min; gallocatechin gallate (GCG) 3.906 min; ECG 4.631 min; and catechin gallate (CG) 6.221 min, respectively (Table S2).

2.4. Determination of Total Phenolic Content (TPC)

The TPC of the samples was determined according to the International Standards Organization (ISO) 14502-1-2005 E procedure using the Folin–Ciocalteu reagent (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). In brief, 1 mL extract was mixed with 5 mL of 10% diluted Folin–Ciocalteu’s reagent and 4 mL of 7.5% Na2CO3. The mixture was then incubated at room temperature for 1 h, and the absorbance was measured at 765 nm using a UV–visible spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Madison, Wisconsin, USA). All samples were analyzed in triplicate. Gallic acid (GAE) (10–100 μg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich) was used as a positive control. The results were expressed as milligrams of GAE per gram of extract (mg GAE/g extract).

2.5. Total Flavonoid Content (TFC)

The TFC was determined using an aluminum chloride colorimetric assay, as described in a previous study [60], with some modifications. In brief, 5 mL extract was mixed with 10 μL of 10% aluminum chloride (Sigma-Aldrich) and 2.0 mL NaOH solution. The mixture was then incubated in the dark at room temperature for 40 min. Absorbance was measured at 510 nm using a UV–visible spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). All samples were analyzed in triplicates. A solution of quercetin (QE) (0–12 mg/mL; lot number: Q4951; Sigma-Aldrich) was used to prepare a standard curve to determine the TFC of the extracts. The results were expressed as milligrams of QE equivalents per gram of extract (mg QE/g extract).

2.6. Determination of Free Radical Scavenging Activities

The free radical scavenging activity of Thai Assam tea extract was determined using the 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) assay [61]. In brief, the sample (50–500 μg/mL) was added to 6.0 × 10−5 mol/L DPPH solution in a 96-well plate. The mixture was then incubated for 30 min at room temperature in the dark. Absorbance was measured at 517 nm using a microplate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Göteborg, Sweden). EGCG concentration at 0.625–10 μg/mL was used as a positive control. The percent scavenging activity (%SA) was calculated by using the following equation:

| %SA=[(sample−blank)blank]×100, | (1) |

where Asample is the absorbance of the DPPH-treated sample at 517 nm and Ablank is the absorbance of DPPH-treated methanol at 517 nm.

The 2,2′-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS) assay was conducted according to a previously described method with some modifications [62]. In brief, 7 mM ABTS (36.0 mg) was dissolved in 10 mL K2S2O8 (2.45 mM), and the solution was incubated at room temperature for 18 h in the dark, resulting in the generation of ABTS+ radicals. After 18 h, the ABTS solution was diluted with methanol to ensure a consistent absorbance of 0.70 ± 0.02 at 734 nm. The sample (20 μL) at 1.25–20 μg/mL was mixed with the solution containing ABTS+ radicals (180 μL) in a 96-well plate. The mixture was then incubated for 30 min at room temperature in the dark. Absorbance was measured at 734 nm using a microplate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific). EGCG at a concentration between 1 and 10 μg/mL was used as a positive control. The %SA was calculated by using the following equation:

| %SA=[(Asample−Ablank)Ablank]×100, | (2) |

where Asample is the absorbance of the sample treated with ABTS at 734 nm and Ablank is the absorbance of ABTS-treated methanol at 734 nm.

The 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) values of the samples in both DPPH and ABTS assays were determined from a graph plotted against the concentration and percentage of inhibition.

2.7. Ferric-Reducing Antioxidant Power (FRAP) Assay

The ability of the tea extracts to chelate ferrous ions was evaluated using a colorimetric method described in a previous study with some modifications [62]. The FRAP reagent was prepared by mixing 2.5 mL of 10 mM TPTZ stock solution, 25 mL acetate buffer (300 mM, pH 3.6), and 2.5 mL 20 mM FeCl3 solution (1:10:1). Then, 50 μL of the sample (0.5 mg/mL) was mixed with 150 μL FRAP reagent in a 96-well plate. The mixture was then incubated for 30 min at room temperature in the dark. The absorbance of the intense blue complex formed after the incubation was measured at 594 nm using a microplate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and the reducing capacity was expressed as μM FeSO4/mg extract.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

All data were obtained from three dependent experiments and are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 10.0.3 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, California, USA) using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Differences at p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Identification and Quantitative Analysis of Thai Assam Tea Extracts

The chromatographic elution of different catechin derivatives and CF in the final extracts of Thai Assam tea is shown in Figure 2. The catechin derivative contents in all extracts are shown in Table 1. UAEFD-TT extracts had the highest total catechins (341.38 ± 0.11 mg/g extract), while UAESD-MT extracts had the lowest (147.13 ± 0.36 mg/g extract). ECG was the most abundant catechin in UAEFD-TT and UAESD-TT extracts (109.63 ± 0.15 and 99.50 ± 0.00 mg/g extract, respectively), whereas CG (0.93 ± 0.05 mg/g extract and 0.47 ± 0.12 mg/g extract) and GC (5.90 ± 0.00 mg/g extract and 5.22 ± 0.01 mg/g extract) were the least abundant in these extracts, respectively. GCG and CG were not detected in the UAEFD-MT and UAESD-MT extracts. However, the CG content among UAESD-TT, UAEFD-ML, and UAESD-ML extracts was not significantly different (p > 0.05) (Table 1). The total catechins can be arranged according to their amounts in the following order: UAEFD-TT > UAESD-TT > UAEFD-ML > UAESD-ML > UAEFD-MT > UAESD-MT.

Figure 2.

Table 1.

Catechin contents in Thai Assam tea extracts.

| Catechins (mg/g extract) | UAEFD-TT | UAESD-TT | UAEFD-ML | UAESD-ML | UAEFD-MT | UAESD-MT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GC | 5.90 ± 0.00a | 5.22 ± 0.01b | 4.49 ± 0.01c | 4.42 ± 0.02d | 3.91 ± 0.01e | 3.55 ± 0.06f |

| EGC | 42.25 ± 0.09a | 37.21 ± 0.01b | 33.64 ± 0.12c | 32.95 ± 0.36d | 23.51 ± 0.17e | 20.57 ± 0.09f |

| C | 28.65 ± 0.05a | 23.41 ± 0.01e | 23.97 ± 0.02d | 23.20 ± 0.00f | 27.89 ± 0.06b | 27.13 ± 0.02c |

| EC | 59.32 ± 0.03a | 36.40 ± 0.00b | 34.91 ± 0.07c | 34.12 ± 0.06d | 22.89 ± 0.06e | 20.39 ± 0.10f |

| EGCG | 93.40 ± 0.17a | 86.32 ± 0.01b | 81.20 ± 0.49c | 80.93 ± 0.06d | 27.32 ± 0.01e | 22.49 ± 0.06f |

| GCG | 1.29 ± 0.04a | 0.81 ± 0.01b | 0.71 ± 0.03c | 0.64 ± 0.06d | ND | ND |

| ECG | 109.63 ± 0.15a | 99.50 ± 0.00b | 94.90 ± 0.07c | 94.09 ± 0.06d | 57.22 ± 0.01e | 53.00 ± 0.15f |

| CG | 0.93 ± 0.05a | 0.47 ± 0.12b | 0.48 ± 0.01b | 0.41 ± 0.00b | ND | ND |

| Total catechins | 341.38 ± 0.11a | 289.34 ± 0.13b | 274.31 ± 0.74c | 270.75 ± 0.27d | 162.74 ± 0.11e | 147.13 ± 0.36f |

Note: Each value is expressed as mean ± standard deviation.

Abbreviation: ND, not detected.

a–fValues in the same row with different superscripts are significantly different (p < 0.05).

3.2. TPC and TFC of the Thai Assam Tea Extracts

The TPC and TFC of the extracts are shown in Table 2. Consistent with the results of catechin contents, the TFC and TPC in UAEFD-TT were higher than those in the other extracts (456.78 ± 4.31 mg GAE/g extract and 333.98 ± 0.83 mg QE/g extract, respectively), suggesting extraction of TT samples using UAE followed by FD increases the yield of the phenolic and flavonoid compounds in the Thai Assam tea extract.

Table 2.

TPC, TFC, and CC of Thai Assam tea extracts.

| Samples | TPC (mg GAE/g extract) | TFC (mg QE/g extract) | CC (mg CF/g extract) |

|---|---|---|---|

| UAEFD-TT | 456.78 ± 4.31a | 333.98 ± 0.83a | 93.20 ± 0.36a |

| UAESD-TT | 434.98 ± 3.33b | 309.69 ± 0.60b | 79.33 ± 0.31b |

| UAEFD-ML | 394.70 ± 2.12c | 247.84 ± 0.82c | 73.03 ± 0.15c |

| UAESD-ML | 334.82 ± 1.16d | 240.91 ± 0.42d | 72.80 ± 0.26c |

| UAEFD-MT | 313.32 ± 2.45e | 190.03 ± 0.62e | 43.00 ± 0.56d |

| UAESD-MT | 247.04 ± 2.57f | 168.76 ± 0.46f | 72.53 ± 0.25c |

Note: Each value is expressed as mean ± standard deviation (n = 3).

a–fValues in the same column with different superscripts are significantly different (p < 0.05).

3.3. Total Caffeine Content (CC) of the Thai Assam Tea Extracts

The CC of the extracts is presented in Table 2. The results showed that the CC in UAEFD-TT samples was the highest (93.20 ± 0.36 mg CF/g extract), whereas that in UAEFD-MT was the lowest (43.00 ± 0.56 mg CF/g extract). The CC content in samples extracted using UAE, followed by FD extracted from TT, was greater than those extracted from ML and MT; however, using the SD method, CC obtained from TT and ML did not show a significant difference (p > 0.05). The amounts of CC can be arranged as follows: UAEFD-TT > UAESD-TT > UAEFD-ML = UAESD-ML = UAESD-MT > UAEFD-MT.

3.4. Free Radical Scavenging and Ferrous Ion Chelating Activities of the Thai Assam Tea Extracts

The antioxidant activities of the extracts were assessed using DPPH, ABTS, and FRAP assays. The DPPH and ABTS assays revealed that UAEFD-TT exhibited strong free radical scavenging ability with IC50 values of 1.31 ± 0.02 μg/mL for DPPH and 7.51 ± 0.03 μg/mL for ABTS compared to the positive control (4.78 ± 0.08 μg/mL of DPPH and 7.36 ± 0.10 μg/mL of ABTS). FRAP assay revealed similar results and UAEFD-TT exhibited remarkably strong ferrous ion chelating ability (324.54 ± 3.33 μM FeSO4/mg extract) than the remaining extracts (Table 3).

Table 3.

Effect of Thai Assam tea extracts on antioxidant activity.

| Samples | DPPH IC50 (μg/mL) | ABTS IC50 (μg/mL) | FRAP (μM FeSO4/mg extract) |

|---|---|---|---|

| UAEFD-TT | 1.31 ± 0.02e | 7.51 ± 0.03f | 324.54 ± 3.33a |

| UAESD-TT | 1.81 ± 0.02d | 8.56 ± 0.04e | 250.64 ± 1.80b |

| UAEFD-ML | 5.58 ± 0.30a | 10.57 ± 0.02c | 132.57 ± 2.33c |

| UAESD-ML | 2.40 ± 0.02c | 9.22 ± 0.02d | 125.03 ± 3.07d |

| UAEFD-MT | 4.59 ± 0.01b | 12.30 ± 0.05b | 115.98 ± 1.64e |

| UAESD-MT | 4.73 ± 0.02b | 13.90 ± 0.05a | 102.20 ± 2.43f |

| EGCG | 4.78 ± 0.08b | 7.36 ± 0.10f | — |

Note: Each value is expressed as mean ± standard deviation (n = 3).

a–fValues in the same row with different superscripts are significantly different (p < 0.05). Values followed by the same letter(s) are not significantly different (p > 0.05) according to Duncan’s multiple range test.

4. Discussion

In the present study, we investigated the effects of the drying method following UAE on the catechin profiles and antioxidant activities of extracts obtained from the leaves of Thai Assam tea at different maturity stages (TT, ML, and MT). The findings demonstrated that UAEFD-TT had the highest catechin content and CC. These extracts also exhibited the highest TPC and TFC and demonstrated the strongest antioxidant activity. The findings suggest that UAE, followed by FD, is an efficient method for extracting antioxidant compounds, and TT is the suitable stage to obtain extracts with enhanced quality.

HPLC analysis revealed high catechin and CCs in TT extracts, followed by ML and MT extracts obtained using UAE and different drying methods. However, FD increased the efficiency of catechins’ yield in the extracts compared to SD [63]. Furthermore, in TT and ML extracts, the levels of EGCC and EGC were higher than those in the MT extracts, whereas GCG and CG were not identified in MT extracts. These findings of this study are consistent with those of a previous study, which showed markedly decreased EGCG content in ML, while EGC content was increased markedly in TT and ML [64]. Previous studies reported that the catechin and CCs depend on the stages of tea leaves with TT containing high EGCG, EGC, ECG, EC, and CF [65–67]. Similar to our findings, GC and GCG contents were the lowest or could not be detected in MT samples [68]. Moreover, the amount of bioactive compounds in tea extracts depends on seasonal variation, harvest method, leaf variety, and genetic variation [7, 64, 68].

UAE can enhance the mass-transfer rate of bioactive compounds during extraction from plant tissues [69], and the use of solvents increases catechin extraction efficiency and reduces extraction time [70]. Ultrasonic extraction is well established. The cell walls in the leaves can be destroyed by the action of the burrows. This resulted in increased extraction yield and reduced extraction solvent [29, 71]. Furthermore, previous studies have reported that a high yield of catechins was attained using 50% ethanol as the extraction solvent [70, 71]. This could be because the solvents increase the surface area under contact between the solvent and cell matrix, leading to increased efficiency of extraction [69]. The frequency, temperature, and power of the ultrasound should also influence the efficiency of the extraction method. The ultrasonic power of 150 W, ultrasound frequency of 37 kHz, and controlled solvent temperature of 30°C were used in our study. These were within the ranges of published optimal conditions for extractions of catechins in green tea, and 20–40 kHz frequency, 28°C–60°C temperature, and 50–461 W power have been shown to improve the extraction efficacy of total catechins in green tea [69, 72]. SD presents advantages such as cheap large-scale production, ease of change in operating conditions, and availability at both laboratory and industrial scales [40]. However, FD is effective in preserving the nutritional contents of powdered products [73]. In this study, we found that FD had a higher efficiency in recovering catechin contents than SD. This could be because low temperatures ensure the better preservation of bioactive compounds. Phenolic compounds are a type of polyphenol that are classified as tannins, propanoids, and flavonoids. Phenolic compounds are powerful chain-breaking antioxidants that may directly contribute to antioxidative activity [74, 75]. These compounds are important constituents of plants, and their radical scavenging ability is attributed to their hydroxyl groups [76]. DPPH and ABTS assays indicate radical scavenging activities, while FRAP assay presents the ability to reduce the ferric ions of the plant extracts [77]. In this study, the results showed that extracts with high TPC and TFC had high antioxidant activities. Consistent with our findings, strong correlations have been reported between the antioxidant capacities and TPC and TFC of the Thai Assam tea extract [78, 79]. These results indicate that the antioxidant activities of the plant extracts are most likely attributed to their polyphenol contents [80]. Previous studies reported that flavonoids have antioxidant, anti-inflammation, and antiarteriosclerotic activities [81]. Moreover, tea flavonoids have high antioxidant and radical scavenging activities [11, 39, 45, 52, 56, 82].

The findings of this study showed that the TT extracts had a higher TPC than the ML and MT extracts. In addition, UAEFD-TT exhibited a significantly higher antioxidant activity and polyphenol content (TPC and TFC). Moreover, the TPC and TFC of Thai Assam tea extract were markedly higher than those reported in previous studies (TPC 391.48 ± 1.16 mg GAE/g extract and TFC 195.02 ± 13.14 mg QE/g extract) [54, 83]. The strong antioxidant activity of UAEFD-TT can be related to its high catechin contents. Furthermore, our findings also showed that the polyphenolic components and antioxidant values decreased with increasing maturity of leaves, which could be attributed to the morphological changes in leaves with age and unique chemical compound transportation within the plant [84]. Furthermore, extraction with aqueous methanol has been reported to contribute to higher antioxidant activity than pure methanol and hot water extraction [85, 86]. Our study is consistent with the study by Rafique et al. [87], who reported that the radical scavenger percentage of 50% ethanol tea extract (77.15%) was similar to that of the 80% ethanol solvent extract (77.70%) [87]. Our results, consistent with a previous report, suggested that different solvents with different polarities also influence the efficiency of the antioxidant activity of tea extract [88–90]. Taken together, we demonstrated that among the different tea preparations, UAEFD-TT had the highest antioxidant effects, catechin contents, TPC, and TFC. The information from this study may be beneficial to the development of Thai Assam tea for health promotion.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, the present study evaluated the efficiency of SD and FD methods following UAE on the yield of catechins in the extracts obtained from Thai Assam tea leaves at different maturity levels (TT, ML, and MT). The results showed that UAEFD-TT had higher catechins, TPC, TFC, CC, and antioxidant activities compared to ML and MT leaf extracts obtained using the same method. This study highlights the importance of UAE, drying methods, and solvent choice in obtaining tea extracts, which contributes to the determination of the quality of Thai Assam tea cultivars. The present study can serve as a springboard to further improvement or development of Thai Assam tea extract, which can be considered as a herbal supplement.

Nomenclature

- HPLC

- High-performance liquid performance chromatography

- UAE

- Ultrasound-assisted extraction

- FD

- Freeze drying

- SD

- Spray drying

- TT

- Top leaves

- ML

- Middle leaves

- MT

- Mature leaves

- DPPH

- 2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl

- ABTS

- 2,2′-Azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid)

- FRAP

- Ferric-reducing antioxidant power

- EGCG

- (−)-Epigallocatechin gallate

- EGC

- (−)-Epigallocatechin

- ECG

- (−)-Epicatechin gallate

- EC

- (−)-Epicatechin

- GC

- Gallocatechin

- C

- Catechin

- CF

- Caffeine

- GCG

- Gallocatechin gallate

- CG

- Catechin gallate

- TFA

- Trifluoroacetic acid

- TPTZ

- 2,4,6-Tris(2-pyridyl)-s-triazine

- TPC

- Total phenolic content

- TFC

- Total flavonoid content

- CC

- Caffeine content

- mg GAE/g extract

- Milligrams of gallic acid equivalent per gram extract

- mg QE/ g extract

- Milligrams of quercetin equivalent per gram extract

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available in the supporting information of this article.

Disclosure

The authors have nothing to report.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

Piyaporn Chueamchaitrakun, Sakan Warinhomhoun, and Chung S. Yang conceptualized the study and performed supervision. Piyaporn Chueamchaitrakun, Sakan Warinhomhoun, Jiraporn Raiputta, and Paryn Na Rangsee performed methodology, investigation, and software. Piyaporn Chueamchaitrakun, Sakan Warinhomhoun, Jiraporn Raiputta, Paryn Na Rangsee, and Chung S. Yang performed validation and formal analysis and contributed resources and reviewed and edited the manuscript. Piyaporn Chueamchaitrakun performed visualization, project administration, and funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by Reinventing University 2023 and has received funding support from The Office of the Permanent Secretary of the Ministry of Higher Education, Science, Research and Innovation.

Supporting Information

Supporting information includes Table S1: Weight of the Thai Assam tea extracts. Table S2: Retention time of catechins and caffeine from Thai Assam tea extract.

References

- 1.Nain C. W., Mignolet E., Herent M. F., et al. The Catechins Profile of Green Tea Extracts Affects the Antioxidant Activity and Degradation of Catechins in DHA-Rich Oil. Antioxidants . 2022;11(9) doi: 10.3390/antiox11091844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang H., Helliwell K. Determination of Flavonols in Green and Black Tea Leaves and Green Tea Infusions by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography. Food Research International . 2001;34(2-3):223–227. doi: 10.1016/s0963-9969(00)00156-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang H., Provan G. J., Helliwell K. Tea Flavonoids: Their Functions, Utilisation and Analysis. Trends in Food Science & Technology . 2000;11(4-5):152–160. doi: 10.1016/S0924-2244(00)00061-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gu X., Cai J., Zhang Z., Su Q. Dynamic Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of Catechins and Caffeine in Some Tea Samples. Annali di Chimica . 2007;97(5-6):321–330. doi: 10.1002/adic.200790018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kowalska J., Marzec A., Domian E., et al. Influence of Tea Brewing Parameters on the Antioxidant Potential of Infusions and Extracts Depending on the Degree of Processing of the Leaves of Camellia Sinensis. Molecules . 2021;26(16):p. 4773. doi: 10.3390/molecules26164773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu Z., Bruins M. E., de Bruijn W. J. C., Vincken J.-P. A Comparison of the Phenolic Composition of Old and Young Tea Leaves Reveals a Decrease in Flavanols and Phenolic Acids and an Increase in Flavonols Upon Tea Leaf Maturation. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis . 2020;86:p. 103385. doi: 10.1016/j.jfca.2019.103385. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Turkmen N., Ferda S., Velioglu Y. S. Factors Affecting Polyphenol Content and Composition of Fresh and Processed Tea Leaves. Akademik Gıda . 2009;7(6):29–40. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gianfredi V., Nucci D., Abalsamo A., et al. Green Tea Consumption and Risk of Breast Cancer and Recurrence—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Nutrients . 2018;10(12):p. 1886. doi: 10.3390/nu10121886. https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/10/12/1886 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tran H. H., Mansoor M., Butt S. R. R., et al. Impact of Green Tea Consumption on the Prevalence of Cardiovascular Outcomes: A Systematic Review. Cureus . 2023;15(12):p. e49775. doi: 10.7759/cureus.49775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu J., Liang D., Li J., et al. Coffee, Green Tea Intake, and the Risk of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Nutrition and Cancer . 2023;75(5):1295–1308. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2023.2178949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang W., Le T., Wang W.-W., Yin J.-F., Jiang H.-Y. The Effects of Structure and Oxidative Polymerization on Antioxidant Activity of Catechins and Polymers. Foods . 2023;12(23):p. 4207. doi: 10.3390/foods12234207. https://www.mdpi.com/2304-8158/12/23/4207 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Almajano M. P., Carbó R., Jiménez J. A. L., Gordon M. H. Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activities of Tea Infusions. Food Chemistry . 2008;108(1):55–63. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.10.040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bernatoniene J., Kopustinskiene D. M. The Role of Catechins in Cellular Responses to Oxidative Stress. Molecules . 2018;23(4):p. 965. doi: 10.3390/molecules23040965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chaiwaree S., Srilai K., Kheawfu K., Thammasit P. Antibacterial Activities of Oral Care Products Containing Natural Plant Extracts From the Thai Highlands Against Staphylococcus aureus: Evaluation and Satisfaction Studies. Processes . 2023;11(9):p. 2768. doi: 10.3390/pr11092768. https://www.mdpi.com/2227-9717/11/9/2768 . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li J., Xiao Q., Huang Y., Ni H., Wu C., Xiao A. Tannase Application in Secondary Enzymatic Processing of Inferior Tieguanyin Oolong Tea. Electronic Journal of Biotechnology . 2017;28:87–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ejbt.2017.05.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lochocka K., Bajerska J., Glapa A., et al. Green Tea Extract Decreases Starch Digestion and Absorption From a Test Meal in Humans: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Crossover Study. Scientific Reports . 2015;5(1):p. 12015. doi: 10.1038/srep12015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang X., Kong F. Evaluation of the In Vitro α-Glucosidase Inhibitory Activity of Green Tea Polyphenols and Different Tea Types. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture . 2016;96(3):777–782. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.7147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Polito C. A., Cai Z. Y., Shi Y. L., et al. Association of Tea Consumption With Risk of Alzheimer’s Disease and Anti-Beta-Amyloid Effects of Tea. Nutrients . 2018;10(5):p. 655. doi: 10.3390/nu10050655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li X. X., Liu C., Dong S. L., et al. Anticarcinogenic Potentials of Tea Catechins. Frontiers in Nutrition . 2022;9:p. 1060783. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.1060783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farrar M. D., Nicolaou A., Clarke K. A., et al. A Randomized Controlled Trial of Green Tea Catechins in Protection Against Ultraviolet Radiation–Induced Cutaneous Inflammation. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition . 2015;102(3):608–615. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.115.107995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakanishi T., Mukai K., Yumoto H., Hirao K., Hosokawa Y., Matsuo T. Anti-inflammatory Effect of Catechin on Cultured Human Dental Pulp Cells Affected by Bacteria-Derived Factors. European Journal of Oral Sciences . 2010;118(2):145–150. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2010.00714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maeda-Yamamoto M., Ema K., Monobe M., et al. The Efficacy of Early Treatment of Seasonal Allergic Rhinitis With Benifuuki Green Tea Containing O-Methylated Catechin Before Pollen Exposure: An Open Randomized Study. Allergology International . 2009;58(3):437–444. doi: 10.2332/allergolint.08-OA-0066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maeda-Yamamoto M., Kawamoto K., Matsuda N., et al. In: Anti-Allergic Catechins of TEA (Camellia Sienesis) Shirahata S., Teruya K., Katakura Y., editors. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Song J.-M., Lee K.-H., Seong B.-L. Antiviral Effect of Catechins in Green Tea on Influenza Virus. Antiviral Research . 2005;68(2):66–74. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2005.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Takahashi T., Kurebayashi Y., Tani K., Yamazaki M., Minami A., Takeuchi H. The Antiviral Effect of Catechins on Mumps Virus Infection. Journal of Functional Foods . 2021;87:p. 104817. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2021.104817. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Song J. M., Kwon T., Lyoo Y. S., Song J.-M. Anti-Infective Potential of Catechins and Their Derivatives Against Viral Hepatitis. Clinical and experimental vaccine research . 2018;7(1):37–42. doi: 10.7774/cevr.2018.7.1.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sang S., Lambert J. D., Ho C.-T., Yang C. S. The Chemistry and Biotransformation of Tea Constituents. Pharmacological Research . 2011;64(2):87–99. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2011.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fan F.-Y., Shi M., Nie Y., Zhao Y., Ye J.-H., Liang Y.-R. Differential Behaviors of Tea Catechins Under Thermal Processing: Formation of Non-Enzymatic Oligomers. Food Chemistry . 2016;196:347–354. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.09.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kumar K., Srivastav S., Sharanagat V. S. Ultrasound Assisted Extraction (UAE) of Bioactive Compounds From Fruit and Vegetable Processing By-Products: A Review. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry . 2021;70:p. 105325. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2020.105325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wen L., Zhang Z., Rai D., Sun D.-W., Tiwari B. K. Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE) of Bioactive Compounds From Coffee Silverskin: Impact on Phenolic Content, Antioxidant Activity, and Morphological Characteristics. Journal of Food Process Engineering . 2019;42(6):p. e13191. doi: 10.1111/jfpe.13191. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vinatoru M. An Overview of the Ultrasonically Assisted Extraction of Bioactive Principles From Herbs. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry . 2001;8(3):303–313. doi: 10.1016/s1350-4177(01)00071-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ashraf G. J., Das P., Sahu R., Nandi G., Paul P., Dua T. K. Impact of Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of Polyphenols and Caffeine From Green Tea Leaves Using High-Performance Thin-Layer Chromatography. Biomedical Chromatography: Biomedical Chromatography . 2023;37(10):p. e5698. doi: 10.1002/bmc.5698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ateş E., Kaya C., Yücel E. E., Bayra M. Effects of Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction Procedure on Total Phenolics, Catechin and Caffeine Content of Green Tea Extracts. Emirates Journal of Food and Agriculture . 2022;34(8) doi: 10.9755/ejfa.2022.v34.i8.2911. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parisi O. I., Puoci F., Restuccia D., Farina G., Iemma F., Picci N. Polyphenols in Human Health and Disease . 2014. Polyphenols and Their Formulations: Different Strategies to Overcome the Drawbacks Associated with Their Poor Stability and Bioavailability; pp. 29–45. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang B., Qu J., Luo S., et al. Optimization of Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of Flavonoids From Olive (Olea Europaea) Leaves, and Evaluation of Their Antioxidant and Anticancer Activities. Molecules . 2018;23(10):p. 2513. doi: 10.3390/molecules23102513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tiwari B. K. Ultrasound: A Clean, Green Extraction Technology. TrAC, Trends in Analytical Chemistry . 2015;71:100–109. doi: 10.1016/j.trac.2015.04.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Afroz Bakht M., Geesi M. H., Riadi Y., et al. Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of Some Branded Tea: Optimization Based on Polyphenol Content, Antioxidant Potential and Thermodynamic Study. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences . 2019;26(5):1043–1052. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2018.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Banerjee S., Chatterjee J. Efficient Extraction Strategies of Tea (Camellia Sinensis) Biomolecules. Journal of Food Science and Technology . 2015;52(6):3158–3168. doi: 10.1007/s13197-014-1487-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Luo Q., Zhang J.-R., Li H.-B., et al. Green Extraction of Antioxidant Polyphenols from Green Tea (Camellia Sinensis) Antioxidants . 2020;9(9):p. 785. doi: 10.3390/antiox9090785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baltrusch K. L., Torres M. D., Domínguez H., Flórez-Fernández N. Spray-Drying Microencapsulation of Tea Extracts Using Green Starch, Alginate or Carrageenan as Carrier Materials. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules . 2022;203:417–429. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.01.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li S., Mao X., Guo L., Zhou Z. Comparative Analysis of the Impact of Three Drying Methods on the Properties of Citrus Reticulata Blanco Cv. Dahongpao Powder and Solid Drinks. Foods . 2023;12(13):p. 2514. doi: 10.3390/foods12132514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sosnik A., Seremeta K. P. Advantages and Challenges of the Spray-Drying Technology for the Production of Pure Drug Particles and Drug-Loaded Polymeric Carriers. Advances in Colloid and Interface Science . 2015;223:40–54. doi: 10.1016/j.cis.2015.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chhabra N., Arora M., Garg D., Samota M. K. Spray Freeze Drying-A Synergistic Drying Technology and Its Applications in the Food Industry to Preserve Bioactive Compounds. Food Control . 2023;110099 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mphahlele R. R., Fawole O. A., Makunga N. P., Opara U. L. Effect of Drying on the Bioactive Compounds, Antioxidant, Antibacterial and Antityrosinase Activities of Pomegranate Peel. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine . 2016;16:143–212. doi: 10.1186/s12906-016-1132-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Roslan A. S., Ismail A., Ando Y., Azlan A. Effect of Drying Methods and Parameters on the Antioxidant Properties of Tea (Camellia Sinensis) Leaves. Food Production, Processing and Nutrition . 2020;2(1):p. 8. doi: 10.1186/s43014-020-00022-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chemat F., Rombaut N., Meullemiestre A., et al. Review of Green Food Processing Techniques. Preservation, Transformation, and Extraction. Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies . 2017;41:357–377. doi: 10.1016/j.ifset.2017.04.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Meneses D., Ruiz Y., Hernandez E., Moreno F. Multi-Stage Block Freeze-Concentration of Green Tea (Camellia Sinensis) Extract. Journal of Food Engineering . 2021;293:p. 110381. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2020.110381. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Khruengsai S., Sripahco T., Pripdeevech P. Volatile Profiles and Antioxidant Activity of Different Cultivars of Camellia Sinensis Var. 2021.

- 49.Khanongnuch C., Unban K., Kanpiengjai A., Saenjum C. Recent Research Advances and Ethno-Botanical History of Miang, a Traditional Fermented Tea (Camellia Sinensis Var. Assamica) of Northern Thailand. Journal of Ethnic Foods . 2017;4(3):135–144. doi: 10.1016/j.jef.2017.08.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Areekul V., Phomkaivon N. Thai Indigenous Plants: Focusing on Total Phenolic Content, Antioxidant Activity and Their Correlation on Medicinal Effects. Current Applied Science and Technology . 2015;15(1):10–23. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Armstrong L., Araújo Vieira do Carmo M., Wu Y., et al. Optimizing the Extraction of Bioactive Compounds From Pu-Erh Tea (Camellia Sinensis Var. Assamica) and Evaluation of Antioxidant, Cytotoxic, Antimicrobial, Antihemolytic, and Inhibition of α-Amylase and α-Glucosidase Activities. Food Research International . 2020;137:p. 109430. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2020.109430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.de Moura C., Kabbas Junior T., Pedreira F. R. d. O., et al. Purple Tea (Camellia Sinensis Var. Assamica) Leaves as a Potential Functional Ingredient: From Extraction of Phenolic Compounds to Cell-Based Antioxidant/Biological Activities. Food and Chemical Toxicology . 2022;159:p. 112668. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2021.112668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lv H.-P., Dai W.-D., Tan J.-F., Guo L., Zhu Y., Lin Z. Identification of the Anthocyanins From the Purple Leaf Coloured Tea Cultivar Zijuan (Camellia Sinensis Var. Assamica) and Characterization of Their Antioxidant Activities. Journal of Functional Foods . 2015;17:449–458. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2015.05.043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Makhamrueang N., Raiwa A., Jiaranaikulwanitch J., Kaewarsar E., Butrungrod W., Sirilun S. Beneficial Bio-Extract of Camellia Sinensis Var. Assamica Fermented With a Combination of Probiotics as a Potential Ingredient for Skin Care. Cosmetics . 2023;10(3):p. 85. doi: 10.3390/cosmetics10030085. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Misra S., Ikbal A. M. A., Bhattacharjee D., et al. Validation of Antioxidant, Antiproliferative, and In Vitro Anti-Rheumatoid Arthritis Activities of Epigallo-Catechin-Rich Bioactive Fraction From Camellia Sinensis Var. Assamica, Assam Variety White Tea, and Its Comparative Evaluation With Green Tea Fraction. Journal of Food Biochemistry . 2022;46(12):p. e14487. doi: 10.1111/jfbc.14487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.de Moura C., Kabbas Junior T., Mendanha Cruz T., et al. Sustainable and Effective Approach to Recover Antioxidant Compounds From Purple Tea (Camellia Sinensis Var. Assamica Cv. Zijuan) Leaves. Food Research International . 2023;164:p. 112402. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2022.112402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ghosh P., Besra S. E., Tripathi G., Mitra S., Vedasiromoni J. R. Cytotoxic and Apoptogenic Effect of Tea (Camellia Sinensis Var. Assamica) Root Extract (TRE) and Two of Its Steroidal Saponins TS1 and TS2 on Human Leukemic Cell Lines K562 and U937 and on Cells of CML and ALL Patients. Leukemia Research . 2006;30(4):459–468. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2005.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Maslov O., Komisarenko M., Kolisnyk Y., Kostina T. Determination of Catechins in Green Tea Leaves by HPLC Compared to Spectrophotometry. Journal of Organic and Pharmaceutical Chemistry . 2021;19(3(75)):28–33. doi: 10.24959/ophcj.21.238177. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Segatz V., Steger M. C., Blumenthal P., et al. Evaluation of Analytical Methods to Determine Regulatory Compliance of Coffee Leaf Tea. Biology and Life Sciences Forum . 2021;6(1):p. 45. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhishen J., Mengcheng T., Jianming W. The Determination of Flavonoid Contents in Mulberry and Their Scavenging Effects on Superoxide Radicals. Food Chemistry . 1999;64(4):555–559. doi: 10.1016/S0308-8146(98)00102-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Limcharoen T., Pouyfung P., Ngamdokmai N., et al. Inhibition of α-Glucosidase and Pancreatic Lipase Properties of Mitragyna Speciosa (Korth.) Havil.(Kratom) Leaves. Nutrients . 2022;14(19):p. 3909. doi: 10.3390/nu14193909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tomasina F., Carabio C., Celano L., Thomson L. Analysis of Two Methods to Evaluate Antioxidants. Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Education . 2012;40(4):266–270. doi: 10.1002/bmb.20617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Saito S. T., Fröehlich P. E., Gosmann G., Bergold A. M. Full Validation of a Simple Method for Determination of Catechins and Caffeine in Brazilian Green Tea (Camellia Sinensis Var. Assamica) Using HPLC. Chromatographia . 2007;65(9-10):607–610. doi: 10.1365/s10337-007-0190-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chen C. N., Liang C. M., Lai J. R., Tsai Y. J., Tsay J. S., Lin J. K. Capillary Electrophoretic Determination of Theanine, Caffeine, and Catechins in Fresh Tea Leaves and Oolong Tea and Their Effects on Rat Neurosphere Adhesion and Migration. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry . 2003;51(25):7495–7503. doi: 10.1021/jf034634b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chen Y., Li Y., Shen C., Xiao L. Topics and Trends in Fresh Tea (Camellia Sinensis) Leaf Research: A Comprehensive Bibliometric Study. Frontiers in Plant Science . 2023;14:p. 1092511. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2023.1092511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lin Y.-L., Juan I. M., Chen Y.-L., Liang Y.-C., Lin J.-K. Composition of Polyphenols in Fresh Tea Leaves and Associations of Their Oxygen-Radical-Absorbing Capacity with Antiproliferative Actions in Fibroblast Cells. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry . 1996;44(6):1387–1394. doi: 10.1021/jf950652k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wang X., Zhu W., Cheng X., et al. The Effects of Circadian Rhythm on Catechin Accumulation in Tea Leaves. Beverage Plant Research . 2021;1(1):1–9. doi: 10.48130/bpr-2021-0008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang L.-Q., Wei K., Cheng H., Wang L.-Y., Zhang C.-C. Accumulation of Catechins and Expression of Catechin Synthetic Genes in Camellia Sinensis at Different Developmental Stages. Botanical Studies . 2016;57(1):p. 31. doi: 10.1186/s40529-016-0143-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Raghunath S., Budaraju S., Gharibzahedi S. M. T., Koubaa M., Roohinejad S., Mallikarjunan K. A.-O. Processing Technologies for the Extraction of Value-Added Bioactive Compounds from Tea . 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Koch W., Kukuła-Koch W., Czop M., Helon P., Gumbarewicz E. The Role of Extracting Solvents in the Recovery of Polyphenols From Green Tea and Its Antiradical Activity Supported by Principal Component Analysis. Molecules . 2020;25(9):p. 2173. doi: 10.3390/molecules25092173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tsai Y. J., Chen B. H. Preparation of Catechin Extracts and Nanoemulsions From Green Tea Leaf Waste and Their Inhibition Effect on Prostate Cancer Cell PC-3. International Journal of Nanomedicine . 2016;11:1907–1926. doi: 10.2147/ijn.S103759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lee L. S., Lee N., Kim Y. H., et al. Optimization of Ultrasonic Extraction of Phenolic Antioxidants From Green Tea Using Response Surface Methodology. Molecules . 2013;18(11):13530–13545. doi: 10.3390/molecules181113530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Roshanak S., Rahimmalek M., Goli S. A. Evaluation of Seven Different Drying Treatments in Respect to Total Flavonoid, Phenolic, Vitamin C Content, Chlorophyll, Antioxidant Activity and Color of Green Tea (Camellia Sinensis or C. Assamica) Leaves. Journal of Food Science and Technology . 2016;53(1):721–729. doi: 10.1007/s13197-015-2030-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Duh P.-D., Tu Y.-Y., Yen G.-C. Antioxidant Activity of Water Extract of Harng Jyur (Chrysanthemum Morifolium Ramat) LWT – Food Science and Technology . 1999;32(5):269–277. doi: 10.1006/fstl.1999.0548. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shahidi F., Janitha P. K., Wanasundara P. D. Phenolic Antioxidants. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition . 1992;32(1):67–103. doi: 10.1080/10408399209527581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Stagos D. Antioxidant Activity of Polyphenolic Plant Extracts. Antioxidants . 2019;9(1):p. 19. doi: 10.3390/antiox9010019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chaves N., Santiago A., Alías J. C. Quantification of the Antioxidant Activity of Plant Extracts: Analysis of Sensitivity and Hierarchization Based on the Method Used. Antioxidants . 2020;9(1):p. 76. doi: 10.3390/antiox9010076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Abu Bakar M. F., Mohamed M., Rahmat A., Fry J. Phytochemicals and Antioxidant Activity of Different Parts of Bambangan (Mangifera Pajang) and Tarap (Artocarpus Odoratissimus) Food Chemistry . 2009;113(2):479–483. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.07.081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jing L. J., Mohamed M., Rahmat A., Bakar M. F. A. Phytochemicals, Antioxidant Properties and Anticancer Investigations of the Different Parts of Several Gingers Species (Boesenbergia Rotunda, Boesenbergia Pulchella Var Attenuata and Boesenbergia Armeniaca) Journal of Medicinal Plants Research . 2010;4(1):27–32. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zekrumah M., Begua P., Razak A., et al. Role of Dietary Polyphenols in Non-Communicable Chronic Disease Prevention, and Interactions in Food Systems: An Overview. Nutrition . 2023;112:p. 112034. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2023.112034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hasnat H., Shompa S. A., Islam M. M., et al. Flavonoids: A Treasure House of Prospective Pharmacological Potentials. Heliyon . 2024;10(6):p. e27533. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e27533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Singh K., Srichairatanakool S., Chewonarin T., et al. Manipulation of the Phenolic Quality of Assam Green Tea Through Thermal Regulation and Utilization of Microwave and Ultrasonic Extraction Techniques. Horticulturae . 2022;8(4):p. 338. doi: 10.3390/horticulturae8040338. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kanlayavattanakul M., Khongkow M., Klinngam W., Chaikul P., Lourith N., Chueamchaitrakun P. Recent Insights Into Catechins-Rich Assam Tea Extract for Photoaging and Senescent Ageing. Scientific Reports . 2024;14(1):p. 2253. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-52781-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Farhoosh R., Golmovahhed G. A., Khodaparast M. H. H. Antioxidant Activity of Various Extracts of Old Tea Leaves and Black Tea Wastes (Camellia Sinensis L.) Food Chemistry . 2007;100(1):231–236. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2005.09.046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Palaiogiannis D., Chatzimitakos T., Athanasiadis V., Bozinou E., Makris D. P., Lalas S. I. Successive Solvent Extraction of Polyphenols and Flavonoids From Cistus Creticus L. Leaves. Oxygen . 2023;3(3):274–286. doi: 10.3390/oxygen3030018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Turkmen N., Sari F., Velioglu Y. S. Effects of Extraction Solvents on Concentration and Antioxidant Activity of Black and Black Mate Tea Polyphenols Determined by Ferrous Tartrate and Folin–Ciocalteu Methods. Food Chemistry . 2006;99(4):835–841. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2005.08.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Rafique S., Murtaza M. A., Hafiz I., et al. Investigation of the Antimicrobial, Antioxidant, Hemolytic, and Thrombolytic Activities of Camellia Sinensis, Thymus Vulgaris, and Zanthoxylum Armatum Ethanolic and Methanolic Extracts. Food Science and Nutrition . 2023;11(10):6303–6311. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.3569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sereshti H., Samadi S., Jalali-Heravi M. Determination of Volatile Components of Green, Black, Oolong and White Tea by Optimized Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction-Dispersive Liquid–Liquid Microextraction Coupled with Gas Chromatography. Journal of Chromatography A . 2013;1280:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2013.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Shaukat H., Ali A., Zhang Y., et al. Tea Polyphenols: Extraction Techniques and its Potency as a Nutraceutical. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems . 2023;7 doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2023.1175893. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zhao C. N., Tang G. Y., Cao S. Y., et al. Phenolic Profiles and Antioxidant Activities of 30 Tea Infusions From Green, Black, Oolong, White, Yellow and Dark Teas. Antioxidants . 2019;8(7):p. 215. doi: 10.3390/antiox8070215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available in the supporting information of this article.