Learn more: PMC Disclaimer | PMC Copyright Notice

. 2024 Jul 29;31(9):756–763. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000002396

This qualitative study highlighted that joint pain was an alarming and surprising symptom of menopause among Latinas, which can negatively impact daily activities and quality of life. There is a need to develop more culturally specific approaches for menopause-related pain management in this underserved population.

Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this qualitative study was to explore the symptom experience and coping strategies for managing joint pain during the menopause transition in urban Latina women.

Methods

We conducted focus groups with 13 English-speaking peri and early postmenopausal Latinas living in Upper Manhattan in New York City in 2014. Eligible participants were self-identified Latinas aged 45 to 60 years with new onset or worsening joint pain and spontaneous amenorrhea, recruited through flyers and snowball sampling. Focus group interviews conducted in English were audiotaped, transcribed, and analyzed by a bilingual research team, using NVivo software (QSR International) to organize and code themes.

Results

On average, participants were aged 51.7 ± 4.8 years and overweight (body mass index of 29.3 ± 6.7 kg/m2); 10 (76.9%) were Puerto Rican, and the last menstrual period was 1 month to 5 years ago. The following four themes emerged: 1) menopause and joint pain are an alarming package; 2) pain disrupts life and livelihood; 3) medical management is unsatisfactory and raises worries about addiction; and 4) home remedies for coping with pain—from maca to marijuana. Despite access to a world-class medical facility in their neighborhood, women seeking pain relief preferred to self-manage joint pain with exercise, over-the-counter products, and other culturally valued home remedies. Many suffered through it.

Conclusions

For midlife Latinas, joint pain symptoms may emerge or worsen unexpectedly as part of the menopause transition and carry distressing consequences for daily activities and quality of life. There is a need to develop more culturally specific approaches for menopause-related pain management in this underserved population.

Nearly 100 years ago Cecil and Archer first observed that “arthritis of the menopause has been one of the most frequent types of arthritis encountered in [our] clinic.”1 Since then, research has shown that joint pain is one of the most common self-reported symptoms of menopause, second only to hot flashes.2–4 According to a recent systematic review and meta-analysis, joint pain or aches occur in 50%-89% of perimenopausal women. 5 Although not well characterized beyond prevalence, several factors have been associated with greater frequency or severity of joint pain during perimenopause: Black and Latina race and ethnicity, higher body mass index (BMI), and negative mood. 5–7 Recent data further suggest that menopause symptoms extend to 5 years after the last menstrual period—early postmenopause.8 Researchers suggest that menopause may exacerbate chronic pain syndromes by triggering a combination of underlying biobehavioral changes.9 However, the experience, etiology, and management of joint pain in perimenopausal women have been underexplored.

Latinas are at high risk for chronic pain and are often undertreated.10 In the United States, Latinas exhibit elevated rates of obesity and menopause symptoms compared to non-Latina White groups,11,12 but studies seldom include pain as a menopause symptom. 13 An estimated 61% of perimenopausal Latinas report joint pain—a similar prevalence to other racial and ethnic groups.14 However, Latinas report more severe chronic pain and fewer pain-free days compared to non-Latina White adults.15,16 However, relatively little is known about how cultural attitudes, behaviors, and practices may differentially influence the pain experience and its management.17

Accumulating evidence from disparate animal, clinical, and epidemiologic studies suggests that estrogen loss induced by oophorectomy, natural menopause, or withdrawal of hormone therapy promotes musculoskeletal pain,18 but its onset, progress, and moderation by other factors is poorly understood.19 Previous focus group work among primarily Mexican-American women has been successful in examining menopausal symptoms and experiences.20 As part of a larger study to characterize the features of newly emergent or exacerbated joint pain in peri- and early postmenopausal women, we conducted focus groups in a diverse sample of urban, midlife women residing in New York City.21 This paper describes the findings of the focus groups conducted with peri- and postmenopausal Latinas recruited from the Northern Manhattan neighborhoods of Washington Heights and Inwood to explore their joint pain experience and pain management strategies.

METHODS

Design

We conducted a descriptive qualitative study guided by a feminist approach in which researchers emphasize the participants’ views, perspectives, and experiences of menopause as well as the interaction between gender and other contextual factors that might influence participant experiences.20,22,23 The focus group method, which brings participants together in small groups to discuss a specific topic of common interest, was chosen as the qualitative approach because of its successful use with women on topics related to women’s health.24

Setting and participants

After approvals by the institutional review board of Columbia University and the Community Engagement Research Center of the Irving Institute for Clinical and Translational Research, participants were drawn from an active volunteer community of women residing immediately surrounding our medical center where according to zip code demographics, the majority of residents are medically underserved, are largely Latino (71%), recent immigrants (51%), and primarily from the Dominican Republic and Puerto Rico.25 Participants were recruited through flyers and mailings distributed to the Community Engagement Research Center core’s registry of community volunteers. Flyers were placed in buildings throughout the Columbia Medical Center as well as affiliated clinics, and schools (ie, school of medicine, nursing, dentistry).

Women between the ages of 45 and 60 years were eligible for inclusion if they: 1) self-identified as Hispanic/Latina; 2) were peri- or early postmenopausal based on reported menstrual irregularity or last menstrual period 3 months to 5 years ago; 3) were experiencing new-onset or worsening musculoskeletal pain/stiffness of the neck, shoulder, fingers, back, hips, knees, or ankles; 4) were not taking hormone therapy or birth control pills; 5) able to read and speak conversational English; and 6) willing to speak about health issues with a group of other research volunteers with a similar background. We included women who were early postmenopausal due to documented data in the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) showing menopause symptoms can extend to 5-year from last menstrual period (LMP). Women were excluded if currently suffering from other conditions such as cancer or recent physical injury, which could impact the course of pain or pain management. Women were also excluded if they reported other comorbid conditions with potential effects on pain (eg, diabetes, depression), or used antidepressants in the last 6 months.

Interested participants contacted the study team by telephone or email to assess eligibility and review the study protocol. Eligible participants were invited to a focus group session in an accessible conference room at the Community Partnership for Health, a resource of Columbia University’s Irving Institute for Clinical and Translational Research. Written informed consent was obtained by the moderator before the focus group discussion.

Data collection procedures

Thirteen volunteers participated in one of five focus groups ranging in size from one to four individuals held between January 2014 and December 2014. Out of respect for those individuals who attended, there was no minimum number required for the interview. At each session, one or two “no-shows” were common due to childcare problems, difficulties with transportation, or work schedules, thus contributing to the very small size of some groups in two cases. Before the start of the focus group interview, an informed consent process was completed, and an investigator-developed questionnaire was used to collect information on demographics (eg, age, Latina background, employment), clinical history, and pain symptoms. Participants self-reported their height and weight, which was used to calculate BMI in kg/m2. Pain was assessed using the short form of the Brief Pain Inventory, which consisted of a front and back body diagram to identify 14 pain locations, four pain severity items (average level, current level, worst and least in the last 24 hours) and seven pain interference items rated on 0 (least) to 10 (worst) scales (general activity, mood, walking, relations with other people, sleep and enjoyment of life). Cronbach alpha coefficients for the pain intensity and interference scales are 0.78-0.96 and 0.83-0.95, respectively.26

Focus group discussions were led using an investigator-developed guide that included rules of conduct and confidentiality. For consistency across all focus groups, the same sequence of discussion topics was used: the menopause experience in general, joint pain symptoms, management strategies, and coping methods during the menopause transition. The same female moderator (N.E.R.) facilitated all focus group discussions with a research assistant (Y.I.C.) who served as an observer and note-taker. The research assistant was a bilingual Latina with extensive experience working with Latino communities in New York City. All focus group sessions were audio recorded and professionally transcribed verbatim. Participants were identified by first name only or an assigned number to maintain anonymity.

The data collection visit lasted approximately 2 hours including the consent process and questionnaires (focus group discussions lasted an estimated 90 minutes). For their participation, participants received a $25 cash payment and a copy of the Menopause Guidebook for Consumers (The North American Menopause Society, 2012). Light refreshments were provided at the group meetings.

Data management and analysis

An emergent content analysis was conducted to identify prominent themes and patterns in the data. Focus group transcripts and audio were entered into NVivo (Qualitative Solutions and Research, Burlington, MA) qualitative software to facilitate the content analysis. Two researchers (Y.I.C. and N.K.R.) independently reviewed transcripts in an iterative process to obtain a sense of the data as a whole.27 Key concepts that related to the four content areas (pain experience, impact on lifestyle, medical management, self-management/coping) were highlighted and organized into smaller codes The researchers discussed each code and labeled them according to the content they represent. Next, the coders met biweekly to define and refine codes until a consensus was reached on a coding scheme. A single coder analyzed the remaining transcripts using the coding scheme. Finally, the codes were organized into themes and quotes identified from the data to exemplify these themes.

Scientific rigor

To enhance study rigor, we focused on the following four criteria established by Lincoln and Guba (1985): credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability.28 To address credibility and confirmability, two coders were involved in the data analysis process. In addition, member checks were conducted by verifying information from one focus group with another. To enhance transferability, we collected sociodemographic data before the start of the focus group to provide a detailed description of the research participant’s background for future researchers and clinicians. An audit trail of the research process and findings was maintained to enhance dependability.

RESULTS

On average, participants were aged 51.7 ± 4.8 years and overweight (BMI was 29.3 ± 6.7 kg/m2); 10 self-identified as Puerto Rican, two as Cuban, and one did not specify (Table 1). Participants had their last menstrual period between 1 month and 5 years ago, with two having undergone hysterectomy without hormone therapy before age 50. Although participants reported joint pain in multiple locations, the most common sites were the back, neck, hands/wrists, and knees with mean pain intensity ranging from 5.4 ± 1.7 (lowest in last 24 hours) to 7.0 ± 2.4 (worst in last 24 hours) on a scale of 1 to 10 (10 being the worst). Although participants rated their overall pain’s interference with general activities as 5.4 ± 2.2 on a scale of 0 (does not interfere) to 10 (completely interferes), interference scores for sleep and enjoyment in life were higher (7.5 ± 2.7 and 6.4 ± 2.4, respectively).

TABLE 1.

Participant characteristics

| Mean ± SD, Median [IQR], or n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age (y) | 51.7 ± 4.8 |

| Latina background | |

| Puerto Rican | 10 (76.9) |

| Cuban | 2 (15.4) |

| Not specified | 1 (7.7) |

| Employment out of the home,a n = 10 | 4 (40.0) |

| Months since LMP,a n = 8 | |

| 0-6 | 3 (37.5) |

| 7-12 | 3 (37.5) |

| >12 | 2 (25.0) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 29.3 ± 6.7 |

| Pain location (more than one possible,a n = 11 per site) | |

| Head | 5 (45.5) |

| Face | 1 (9.1) |

| Neck | 8 (72.7) |

| Chest | 1 (9.1) |

| Abdomen | 3 (27.3) |

| Shoulders | 5 (45.5) |

| Arms | 4 (36.4) |

| Hands/wrists | 7 (63.6) |

| Hips | 4 (36.4) |

| Legs | 4 (36.4) |

| Knee | 6 (54.5) |

| Foot | 4 (36.4) |

| Back | 9 (81.8) |

| Buttock | 3 (27.3) |

| Pain intensity,a n = 11 | |

| Worst pain last 24 h | 7.0 ± 2.4 |

| Least pain last 24 h | 5.4 ± 1.7 |

| Average pain | 6.1 ± 1.4 |

| Pain right now | 5.0 ± 2.5 |

| Pain Interference,a n = 11 | |

| General activity | 5.4 ± 2.2 |

| Mood | 5.7 ± 2.4 |

| Walking ability | 5.4 ± 2.8 |

| Normal walk | 4.9 ± 2.1 |

| Relations with other people | 4.9 ± 3.6 |

| Sleep | 7.5 ± 2.7 |

| Enjoyment of life | 6.4 ± 2.4 |

Note. Pain was assessed using the short form of the Brief Pain Inventory,25 which consisted of a front and back body diagram to identify pain locations, four pain intensity/severity items, and seven pain interference items rated on 0 (least) to 10 (worst) scales.

IQR, interquartile range; LMP, last menstrual period.

aThe number of participants that answered this question is noted here and differs from 13.

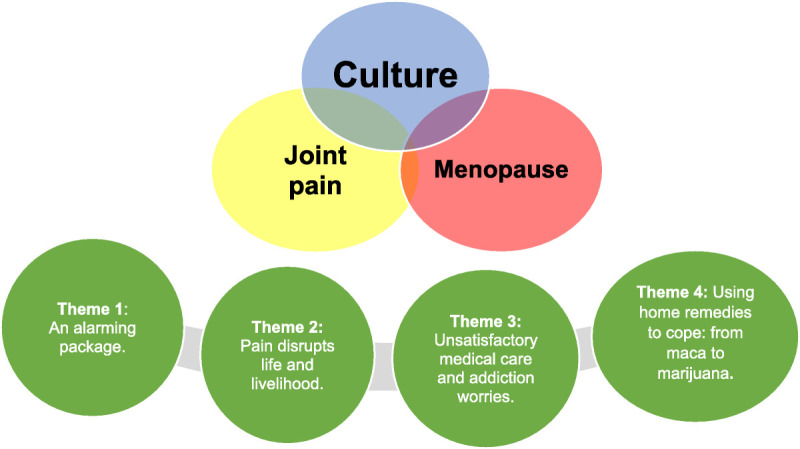

Figure 1 illustrates the four major themes that emerged from the focus group interviews: 1) menopause and joint pain are an alarming surprise package; 2) pain disrupts life and livelihood; 3) medical management is unsatisfactory and raises worries about addiction; 4) using home remedies to cope: from maca to marijuana.

FIG. 1.

Theme #1: Joint pain is an alarming part of the menopause package

This theme refers to participants’ descriptions of the sudden and disturbing emergence of joint pain and stiffness during perimenopause and early postmenopause. Joint pain typically involved more than one area and was described as an unexpected, confusing symptom noted during the menopausal transition. One participant stated: “I went through this, I turned 50 and all of a sudden everything changed. I stopped getting my period; I started getting all these aches in my knees and my wrists and right here [points to knuckles].” This confusion about the sudden emergence of pain and its etiology was further described by another participant:

“I never had any problems. It’s just all of a sudden, menopause, torn meniscus, back problem… arthritis comes with menopause too, doesn’t it? Isn’t it like a package? A third participant added, “the pain is excruciating but I never put the pain and the menopause together. No. I never thought that menopause gives you pain.”

The re-emergence of joint pain and stiffness during perimenopause was also common. Those with existing pain reported it worsening with menopause. One participant described it as follows: “so then it went away [sciatica when she was in her 20s]. Fine. It didn’t bother me at all and I kept dancing and everything. And all of a sudden [age 51], it came back with a vengeance.”

Regardless of onset, joint pain was often viewed as severe and described in vivid terms. Several participants likened their pain experience to being physically attacked: “I feel like they’ve beaten me up—like somebody just came and beat me up.” Another said, “I’ll get like a throbbing in my hands… like somebody is in there… and I’ll say: Hey, get out!… I’m telling it “Get away, get away!”

Theme #2. “I can’t lose my job”—pain disrupts life and livelihood

The distressing impact of pain symptoms on daily activities and quality of life was notable. Most participants reported that pain symptoms interfered substantially with their work, family relationships, and household tasks (eg, cooking, and cleaning). Concerning the workplace, one participant stated, “I am a licensed esthetician and I work standing up…so it’s affecting my livelihood because I can’t stand up.” In another focus group, a participant who was a telemarketer supervisor stated:

“I stand up walking the floor all night, so my knees, I’m popping Ibuprofens all the time. I’ve got bills to pay, I cannot take off from work. The way it is now with jobs, I can’t lose my job.”

Other focus group members described how pain had robbed them of leisure time activities or enjoyable work at home. One woman said,

“Sometimes I’m fine and I feel great and I want to do so many things around my house because I’m in my new apartment. I can’t get to them because the (hip/leg) pain is so excruciating.” Another woman said, “Oh God, going to the movies, it’s my knees…. they end up throbbing and throbbing and throbbing and I can’t take that.”

Later in the same session, this participant disclosed how profound her disability had become: “Sometimes I can’t even sit on the toilet. I literally have to pull my pants down and squat over the toilet like a man…or else I can’t get up. I don’t even try to get in the bathtub.” In another case, pleasant household duties became untenable: “Even my children have noticed. ‘What’s wrong with you? You’re not the same no more.’ I don’t want to cook, and I used to love to cook, especially Sunday.” Another woman revealed how enjoyable duties had been relinquished and reallocated to family members: “I used to turn on the (salsa) music in the house and clean and dance, but it’s not happening… I can’t… my husband and my son does it (housekeeping).”

Theme #3: Unsatisfactory medical care and fear of addiction

Participants sought multiple medical treatments from different sources for their pain including analgesics, steroid injections, physical therapy, and chiropractic treatments. The results have been disappointing: “I did the physical therapy, didn’t do crapola. So, I’m like, ‘Okay, well what’s my other option?’ So now I’m seeing a specialist for the spine and they’re injecting some kind of pain management.” Referrals from primary care providers to rheumatologists and pain specialists were also mentioned as were visits to the emergency room when pain became severe. One participant shared, “they gave me OxyContin and they would shoot me up with Demerol when I’d go in the hospital because I couldn’t move.” Although some participants were prescribed opioids, they were wary of this option. One participant stated, “the pain got so bad my doctor tried to get me on Percocet, but I told him, ‘I can’t, because I’m working and that puts me to sleep.’ So, I told him I can’t mess with that.”

Menopausal hormone/estrogen therapy was also viewed as circumspect, or met with outright rejection, even from two women who had undergone hysterectomy before age 50. Comments such as, “I don’t take any of that. They say that’s not good for you” and “Why do I need that for? I wouldn’t go near it” were common. Women speculated that estrogen therapy was harmful to bones, caused weight gain, and might still be experimental and even addictive. As one participant put it, “I mean, I know that science and medicines (estrogen therapy options) have come a long way, but I also don’t want to get hooked on anything.”

In general, women felt short-changed by their healthcare providers owing to unsatisfactory advice for coping with menopause and joint pain. One participant revealed: “I pop two 800 milligrams each, that’s 1,600 milligrams. And my doctor, he already told me, he don’t give me a prescription for ibuprofen, he said, ‘You need to stop it.’” Another expressed frustration when stating, “So why don’t these doctors give you a paper telling you, ‘Listen, this might happen,’ so that you can know.” A third woman questioned the physician’s approach:

“Why doesn’t he just take care of what the problem is instead of just giving you medication? For the joint pain, there’s nothing.”

A fourth participant remarked: “But he’s not really that helpful (her primary care physician). You know? [Chuckle]. I mean he’ll tell me it’s going to be okay. Tomorrow will be another day.”

Several women described taking the initiative and seeking out care from multiple specialists for a second opinion or when treatments proved ineffective. One participant explained, “Then I said let me go to a physical therapist—someone else, because this orthopedic doctor wasn’t—I mean come on… I took the medicine but then I’m still getting the pain.” Another woman was skeptical when told by an orthopedic specialist that she needed a hip replacement: “and I said, ‘it better be like Alex Rodriguez… I better be able to slide into bases like he does.’ And then I went to a chiropractor.” In another case, a participant speculated: “So maybe I should find another doctor, someone who’s actually going to sit down and listen to me.”

Theme #4. Coping with pain: From maca to marijuana

While participants perceived some medical treatments negatively (eg, opioids), they enthusiastically described self-management strategies including exercise, home remedies, prayer, and in one case, marijuana for their pain. Physical activities such as swimming, salsa dancing, walking, and yoga provided physical and mental relief. For instance:

“…my daughter is in the army and in her housing development they got a gym. Man, and for those two weeks, I was on that treadmill and everything, I felt so much better afterward, I had more energy, I had a better attitude.”

Most women combined exercise with daily chores as opportunities to enhance physical fitness (eg, walking to the grocery store, watching Spanish cable TV exercise shows while housecleaning). One woman added that a $25 gym membership was available at the local YMCA to Medicaid recipients and there were various group exercise classes.

In addition to physical activity, home remedies were popular for pain relief in the form of medicated salves, powders, oils, and teas. One such remedy was maca, “Well I was taking maca, which I have to get some more. It’s a powder. It comes from South America.” Women also used over-the-counter products like Vicks VapoRub at the back of the neck and forehead, Epsom salts in the bath, and lidocaine gel patches for knees and back pain. Other home remedies cited were Woodlock oil, lemon balm tea, and an anesthetic salve purchased in bodegas referred to as “ubre” for sore muscles. Agua de Azahar (orange blossom water) was used to reduce anxiety. One participant revealed that she regularly used cannabis and cannabis-derived products for pain relief:

“I have one (home remedy) and it contains THC and it just works, and it’s fabulous, from the mood to the pain, like I tell you, I don’t pop pills… I go green … I don’t feel no pain, everything keeps moving.”

Participants noted that health providers often overlooked home remedies leaving them to self-manage their pain because there are no other options: “There’s a lot of home remedies, honey, that the doctors don’t have a clue about that work… because according to them, like well, you’re going to be, this is the way you’re going to stay.”

Regardless of home remedy preferences, emotional support from family and friends and/or their religious faith was an important strategy for coping with pain. Sympathetic husbands and friends with similar pain problems were cited as valuable allies: “I have friends, you know, the gatherings. It’s great because it’s like a big party. There’s a celebration there and we have groups like this too, small groups, events where we talk, and we exchange.” Two participants relied on prayer as a coping strategy, with one participant stating, “I pray. I get involved sometimes with praying with a group.” Another said, “I don’t go to church but I’m always praying.”

Finally, stoicism was also implied as a coping strategy when all else failed. One participant summed up that her advice for coping with joint pain and stiffness was to “figure it out for themselves.” Across focus groups, women noted they simply had to “deal with it.”

DISCUSSION

The prevalence of somatic symptoms during menopause, including hot flashes, musculoskeletal pain, fatigue, and headache has been shown to vary across cultures.2,29 This qualitative exploratory study adds to the literature on menopausal joint pain and stiffness by providing insights into the lived experience, health care options, and pragmatic management strategies of Latinas residing in the Washington Heights area of New York City. Consistent with prior research on joint pain in predominantly White, middle-class midlife women,5 participants reported experiencing joint pain or stiffness in multiple sites including wrists, knees, and back. Analyses of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey showed that Mexican Americans with chronic pain report more pain sites than non-Latino White participants.17 While studies have shown that over 60% of perimenopausal Latinas experience joint pain,14,30 our analysis revealed that for most focus group participants, it was an unexpected and alarming part of the menopause transition. Moreover, among women with existing pain, joint pain worsened during perimenopause. This is consistent with quantitative studies noting a higher pain severity score around the final menstrual period.31 Moreover, a recent meta-analysis found a nearly 2-fold greater odds of musculoskeletal pain among perimenopausal women compared to postmenopausal women.5 Our findings aligned with a recent study by Lu and colleagues (2020) indicating that the severity of musculoskeletal pain increased linearly as women traversed from pre- to peri- to postmenopause.5

While Latinas report less chronic pain than non-Latina white women, they report a greater severity of pain.16,31 Participants reported moderate pain on the Brief Pain Inventory, yet across all focus groups, the nature of the narratives suggested a high level of severe pain. This finding suggests that the use of brief questionnaires may not adequately capture the pain experience in peri- and early postmenopausal Latinas. Taken together, our results underscore the need for clinicians and researchers to educate Latinas on the emergence and etiology of joint pain during perimenopause, and assess joint pain more accurately in this population.

Epidemiologic studies have reported that bodily pain is associated with reduced physical functioning and quality of life during perimenopause.32 A major theme in this study was the adverse influence of perimenopausal pain on daily activities and quality of life among Latinas. Joint pain limited participants’ ability to engage in leisure-time activities such as dancing and going to the movies. Relinquishment of enjoyable aspects of the traditional homemaker role such as cooking on Sundays was distressing. For some respondents, basic functions such as sitting on the toilet or sleeping through the night were compromised. Chronic musculoskeletal pain is a leading cause of disability, unemployment, and reduced participation in life activities.33,34 This is consistent with our findings here that among participants with outside employment, joint pain interfered with their ability to effectively function in the workplace. Recent data suggest that menopause symptoms may result in an annual loss of $1.8 billion in wages in the United States.35

While focus group participants sought medical care for pain management, their pain treatment options were limited and made them feel uneasy. Moreover, after seeking care, the pain remained uncontrolled which added to their skepticism. Differences have been identified between Latino and non-Latino White patients in treatment expectations and use of pain medications.10 Studies have shown that Latinos have shorter clinic visits than non-Latino White patients when presenting with pain.36 Moreover, Black and Latino patients are less likely to be prescribed analgesic medications, and when prescribed, receive a lower medication dose.17,37 Our finding that Latina women are concerned about the risk of addiction to pain medications supports earlier work showing that Latinas prefer pain self-management (versus medical treatments) and view pain medication negatively.38

Notably, participants also viewed menopause hormone therapy (MHT), in a similar light. To our knowledge, worry about estrogen addiction at menopause has seldom been voiced as a reason for nonuse despite potential benefits for improving joint-related pain.39–41 In his accompanying commentary regarding the incremental improvements in joint pain observed in the estrogen-only arm in the Women’s Health Initiative trial,42 Kaunitz (2013) suggested that “evidence-based clinicians may choose to selectively offer perimenopausal and recently postmenopausal women with new-onset joint symptoms a trial of HT after counseling such women that the use of HT for this indication is best considered off-label.”42 Although we did not explore the factors that contribute to these negative views of MHT, further study would seem warranted; particularly, for those with surgically induced early menopause, as was the case for two of our participants. To what extent this is a common attitude among midlife Latinas is unclear but suggests the need for improved community resources and greater outreach about the benefits of MHT during the menopause transition.

In this study, exercise was frequently reported as a self-management strategy for joint pain. Low-impact physical activities such as walking, yoga, and swimming have been shown to ease joint pain and improve quality of life.43,44 Although Latinos have the highest rate of physical inactivity in the US both in part due to a lack of access to safe spaces for physical activity and low-cost or free resources such as gym memberships or classes,45 participants in our study proved to be savvy in finding ways to incorporate inexpensive exercise into their daily activities for pain relief. To what extent their engagement with the University Medical Center neighborhood community resources influenced health efficacy decisions is unclear but may have been a factor in these positive actions.

Our focus group findings support prior reports that Latinas rely on traditional or culturally specific remedies for pain care46; one of these remedies was maca. Recent data have shown that Lepidium meyenii (maca), a plant indigenous to the Peruvian Andes, contains bioactive compounds that may alleviate inflammatory pain.47 Another commonly used product among focus group participants was manteca de ubre (udder balm), a topical analgesic made in Puerto Rico. Participants felt that their traditional remedies are valid treatments that health providers do not always consider, suggesting the importance of shared decision making for pain management and discussing various complementary options during clinical encounters. Considering the volume of evidence indicating that psychological factors influence pain perception, it is reasonable to assume that cultural beliefs about pain underlie variations in pain experience and management among people of different cultural backgrounds.48

Although individuals with joint pain are more likely to report depressive symptoms and anxiety,49 participants in this study did not directly report these symptoms as a consequence of pain but rather alluded to impaired psychological mood and well-being because of reduced quality of life. The well-documented influence of both stoicism and religious faith on Latinos coping with the consequences of chronic pain was evident in the transcripts. Religious coping has been correlated to active coping (eg, activities diverting attention from pain) and psychological well-being among Latinos with arthritis.46 Religiosity has also been related to more favorable health outcomes among midlife Latinas.50 For example, in SWAN, Latinas were more likely to report that faith brought them comfort in times of adversity, and low levels of religiosity and faith were associated with a greater incidence of metabolic syndrome.51

Limitations and strengths

Our findings should be interpreted in the context of important limitations. This study included English-speaking Latinas from the Washington Heights and Inwood neighborhoods of New York City, who were mainly Puerto Rican and/or were either born or have lived in the continental US for more than 10 years, limiting the transferability of results. Additionally, women varied in age and staging of the menopause transition, which can further limit generalizability. Given the demonstrated influence of elevated BMI on joint pain,5 the body weight features of the study cohort may have also played a role in joint pain symptom severity. Findings may differ for Latinas in other geographic settings, first-generation immigrants, or individuals living in the US. for fewer than 10 years. Moreover, we did not assess country of birth or the level of acculturation as a pain modifier, which have been shown to influence reports of other menopause symptoms among Latinas in SWAN.13,51,52 Additionally, we used a qualitative descriptive approach, which limits interpretation because of its exploratory nature.53 Finally, findings that are nearly a decade old would not in many cases provide useful insights for contemporary practice or future research directions. However, very little has changed in terms of our understanding of cultural influences on menopause symptoms, especially related to joint pain and arthralgias, as evidenced by results from a 2020 global analysis,5 a 2021 review of menopause symptoms in US Latinas,54 and a 2022 summary of findings from the iconic SWAN study that addressed the paucity of research on the sociocultural and structural factors contributing to the health disparities in menopause symptoms among racially and ethnically minoritized US populations.7 At the same time, social media use, which was not assessed in this study, has escalated during the last 10 years, especially after COVID-19, and may have further reinforced both positive and negative cultural influences on menopause symptoms and coping strategies in midlife Latinas such as familismo (loyalty and respect for family values) on the one hand, and distrust and fear of medical personnel on the other.55 To what extent an increased use of social media would have altered these findings is unknown, but additional research is needed.

Strengths of this study include its focus on Latinas—an underrepresented group in menopause research. Another strength is the inclusion of a bilingual (English, Spanish) Latina from New York City on the research team, which can enhance trust with participants and better convey the meaning of participants’ experiences. Although the research proposal was reviewed by the Columbia Medical Center’s Community Engagement Advisory Committee composed of researchers, practitioners, and community members, in the future, we recommend that a woman from the community be an active member of the research team.

CONCLUSIONS

Joint pain is a public health concern and significantly impacts health care utilization, quality of life, and health outcomes of minoritized populations.56 Multiple biological, psychological, and social factors contribute to the experience of pain.57 This qualitative study highlighted the emergence of pain symptoms among Latinas during perimenopause and early postmenopause, as well as the negative impact of pain on daily activities and quality of life. We found that joint pain was an alarming and surprising symptom during the menopause transition. Additionally, such pain interfered with leisure-time activities, work, and social roles. Finally, this study contributed to the current knowledge of self-management strategies for joint pain among perimenopausal Latinas. Latinas felt unsatisfied with their management options and sought their coping strategies. Future studies in other geographic settings and among Latinas from different backgrounds (eg, Latino subgroup, language, immigration status) are necessary to confirm study findings and identify additional sociocultural factors that may impact pain and quality of life during perimenopause. These findings will facilitate the development of more specific pain prevention and treatment strategies.

Acknowledgments

We thank the women of Washington Heights and Inwood neighborhoods in Northern Manhattan who participated as research volunteers. We thank Valentina Marginean, BSN-RN for her editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Previously presented: Reame NE, Cortes Y, Altemus M. Joint pain in urban perimenopausal Hispanic women: a pilot study of cultural influences, International Menopause Society. 14th World Congress on Menopause. Cancun, Mexico. May 2014.

Funding/support: This study was supported by the National Institute on Aging Translational Research Institute on Pain in Later Life (TRIPPL) grant #5P30AG022845-09 (Reid, PI); National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, formerly the National Center for Research Resources, through grants # UL1TR000040, Training Nurse Scientists in Interdisciplinary and Translational Research in the Underserved (TRANSIT), US Dept of Health and Human Services Health Resources and Services Administration Grant # D09HP14667 (Reame, PI).

Financial disclosures/conflicts of interest: Yamnia I Cortés receives current institutional funding from National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and has received past institutional funding from National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities. Nancy Reame receives funding from Astellas Pharma, has received a consultation fee from the University of Iowa to review a NIH grant application, and has received past funding from Diva Cup International and Organon Inc. Margaret Altemus has nothing to disclose.

Disclaimer: The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIA or NIH.

ORCID ID: Yamnia I. Cortés, https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1520-2775

Contributor Information

Margaret Altemus, Email: margaret.altemus@yale.edu.

Nancy E. Reame, Email: nr2188@columbia.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Russell C, Archer BH. Arthritis of the menopause: a study of fifty cases. JAMA 1925;84:75–79. 10.1001/jama.1925.02660280001001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gold E Sternfeld B Kelsy J, et al. The relation of demographic and lifestyle factors to symptoms in a multiracial/ethnic population of women. Am J Epidemiol 2000;152:463–473. 10.1093/aje/152.5.463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Freeman EW, Sammel MD, Lin H, Gracia CR, Kapoor S. Symptoms in the menopausal transition: hormone and behavioral correlates. Obstet Gynecol 2008;111:127–136. 10.1097/01.AOG.0000295867.06184.b1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heinemann K, Rubig A, Strothmann A, Nahum GG, Heinemann LA. Prevalence and opinions of hormone therapy prior to the Women’s Health Initiative: a multinational survey on four continents. J Womens Health 2008;17:1151–1166. 10.1089/jwh.2007.0584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lu CB Liu PF Zhou YS, et al. Musculoskeletal pain during the menopausal transition: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neural Plast 2020;2020:8842110. 10.1155/2020/8842110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Szoeke CE, Cicuttini FM, Guthrie JR, Dennerstein L. The relationship of reports of aches and joint pains to the menopausal transition: a longitudinal study. Climacteric 2008;11:55–62. 10.1080/13697130701746006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harlow SD Burnett-Bowie SAM Greendale GA, et al. Disparities in reproductive aging and midlife health between Black and White women: the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN). Womens Midlife Health 2022;8:3. 10.1186/s40695-022-00073-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.El Khoudary SR McClure CK VoPham T, et al. Longitudinal assessment of the menopausal transition, endogenous sex hormones, and perception of physical functioning: the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2014;69:1011–1017. 10.1093/gerona/glt285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rousseau ME, Gottlieb SF. Pain at midlife. J Midwifery Womens Health 2004;49:529–538. 10.1016/j.jmwh.2004.08.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Institute of Medicine Committee on Advancing Pain Research, Care, and Education . Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and Research. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US); 2011. doi: 10.17226/13172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schnatz PF, Serra J, O’Sullivan DM, Sorosky JI. Menopausal symptoms in Hispanic women and the role of socioeconomic factors. Obstet Gynecol Surv 2006;61:187–193. 10.1097/01.ogx.0000201923.84932.90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Avis NE, Colvin A. Disentangling cultural issues in quality of life data. Menopause 2007;14:708–716. 10.1097/gme.0b013e318030c32b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Green R Polotsky AJ Wildman RP, et al. Menopausal symptoms within a Hispanic cohort: SWAN, the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. Climacteric 2010;13:376–384. 10.3109/13697130903528272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reed SD Lampe JW Qu C, et al. Premenopausal vasomotor symptoms in an ethnically diverse population. Menopause 2014;21:153–158. 10.1097/GME.0b013e3182952228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grubert E, Baker TA, McGeever K, Shaw BA. The role of pain in understanding racial/ethnic differences in the frequency of physical activity among older adults. J Aging Health 2013;25:405–421. 10.1177/0898264312469404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Racial/ethnic differences in the prevalence and impact of doctor-diagnosed arthritis—United States, 2002. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2005;54:119–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hollingshead NA, Ashburn-Nardo L, Stewart JC, Hirsh AT. The pain experience of Hispanic Americans: a critical literature review and conceptual model. J Pain 2016;17:513–528. 10.1016/j.jpain.2015.10.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gibson CJ, Li Y, Bertenthal D, Huang AJ, Seal KH. Menopause symptoms and chronic pain in a national sample of midlife women veterans. Menopause 2019;26:708–713. 10.1097/GME.0000000000001312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pang H Chen S Klyne DM, et al. Low back pain and osteoarthritis pain: a perspective of estrogen. Bone Res 2023;11:42. 10.1038/s41413-023-00280-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Villarruel AM, Harlow SD, Lopez M, Sowers M. El cambio de vida: conceptualizations of menopause and midlife among urban Latina women. Res Theory Nurs Pract 2002;16:91–102. 10.1891/rtnp.16.2.91.53002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Altemus M LM, Cortés YI, Reame N. Musculoskeletal pain in perimenopause: a qualitative study. Menopause 2013;20:1333. Abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Woods NF, Mitchell ES. Anticipating menopause: observations from the Seattle Midlife Women’s Health Study. Menopause 1999;6:167–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Im EO, Meleis AI, Park YS. A feminist critique of research on menopausal experience of Korean women. Res Nurs Health 1999;22:410–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krueger RA. Analyzing focus group interviews. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2006;33:478–481. 10.1097/00152192-200609000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.King LHK Dragan KL Driver CR, et al. Community Health Profiles 2015, Manhattan Community District 12: Washington Heights and Inwood. The New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. 2015;12:1–16. Available at: https://www.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/data/20. Accessed June 24, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Atkinson TM Mendoza TR Sit L, et al. The Brief Pain Inventory and its “pain at its worst in the last 24 hours” item: clinical trial endpoint considerations. Pain Med 2010;11:337–346. 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2009.00774.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 2005;15:1277–1288. 10.1177/1049732305276687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lincoln Y, Guba EG. Naturalistic inquiry. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1985 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sievert L, Anderson D, Melby M, Obermeyer C. Methods used in cross-cultural comparisons of somatic symptoms and their determinants. Maturitas 2011;70:127–134. 10.1016/j.maturitas.2011.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reed SD Lampe JW Qu C, et al. Self-reported menopausal symptoms in a racially diverse population and soy food consumption. Maturitas 2013;75:152–158. 10.1016/j.maturitas.2013.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee YC Karlamangla AS Yu Z, et al. Pain severity in relation to the final menstrual period in a prospective multiethnic observational cohort: results from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. J Pain 2017;18:178–187. 10.1016/j.jpain.2016.10.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gerber LM, Chiu YL, Verjee M, Ghomrawi H. Health-related quality of life in midlife women in Qatar: relation to arthritis and symptoms of joint pain. Menopause 2016;23:324–329. 10.1097/GME.0000000000000532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arendt-Nielsen L, Fernandez-de-Las-Penas C, Graven-Nielsen T. Basic aspects of musculoskeletal pain: from acute to chronic pain. J Man Manip Ther 2011;19:186–193. 10.1179/106698111X13129729551903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cimmino MA, Ferrone C, Cutolo M. Epidemiology of chronic musculoskeletal pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2011;25:173–183. 10.1016/j.berh.2010.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Faubion SS Enders F Hedges MS, et al. Impact of menopause symptoms on women in the workplace. Mayo Clin Proc 2023;98:833–845. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2023.02.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ly DP. Racial and ethnic disparities in the evaluation and management of pain in the outpatient setting, 2006-2015. Pain Med 2019;20:223–232. 10.1093/pm/pny074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rasu RS, Knell ME. Determinants of opioid prescribing for nonmalignant chronic pain in US outpatient settings. Pain Med 2018;19:524–532. 10.1093/pm/pnx025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Torres CA, Thorn BE, Kapoor S, DeMonte C. An examination of cultural values and pain management in foreign-born Spanish-speaking Hispanics seeking care at a federally qualified health center. Pain Med 2017;18:2058–2069. 10.1093/pm/pnw315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barnabei VM Cochrane BB Aragaki AK, et al. Menopausal symptoms and treatment-related effects of estrogen and progestin in the Women’s Health Initiative. Obstet Gynecol 2005;105(5 Pt 1):1063–1073. 10.1097/01.AOG.0000158120.47542.18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Welton AJ Vickers MR Kim J, et al. Health related quality of life after combined hormone replacement therapy: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2008;337:a1190. 10.1136/bmj.a1190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chlebowski RT Cirillo DJ Eaton CB, et al. Estrogen alone and joint symptoms in the Women’s Health Initiative randomized trial. Menopause 2013;20:600–608. 10.1097/GME.0b013e31828392c4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kaunitz AM. Should new-onset arthralgia be considered a menopausal symptom? Menopause 2013;20:591–593. 10.1097/GME.0b013e31828a6a3d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bartels EM Juhl CB Christensen R, et al. Aquatic exercise for the treatment of knee and hip osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;3:CD005523. 10.1002/14651858.CD005523.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Slagter L, Demyttenaere K, Verschueren P, De Cock D. The effect of meditation, mindfulness, and yoga in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Pers Med 2022;12:1905. 10.3390/jpm12111905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Larsen BA, Pekmezi D, Marquez B, Benitez TJ, Marcus BH. Physical activity in Latinas: social and environmental influences. Womens Health (Lond) 2013;9:201–210. 10.2217/whe.13.9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Abraido-Lanza AF, Vasquez E, Echeverria SE. En las manos de Dios [in God’s hands]: religious and other forms of coping among Latinos with arthritis. J Consult Clin Psychol 2004;72:91–102. 10.1037/0022-006X.72.1.91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Singh N Barnych B Morisseau C, et al. N-Benzyl-linoleamide, a constituent of Lepidium meyenii (Maca), is an orally bioavailable soluble epoxide hydrolase inhibitor that alleviates inflammatory pain. J Nat Prod 2020;83:3689–3697. 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.0c00938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lasch KE. Culture, pain, and culturally sensitive pain care. Pain Manag Nurs 2000;1(3 Suppl 1):16–22. 10.1053/jpmn.2000.9761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hoogeboom TJ, den Broeder AA, Swierstra BA, de Bie RA, van den Ende CH. Joint-pain comorbidity, health status, and medication use in hip and knee osteoarthritis: a cross-sectional study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012;64:54–58. 10.1002/acr.20647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Allshouse AA Santoro N Green R, et al. Religiosity and faith in relation to time to metabolic syndrome for Hispanic women in a multiethnic cohort of women-Findings from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN). Maturitas 2018;112:18–23. 10.1016/j.maturitas.2018.03.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Green R, Santoro N. Menopausal symptoms and ethnicity: the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. Womens Health (Lond) 2009;5:127–133. 10.2217/17455057.5.2.127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Green R Santoro NF McGinn AP, et al. The relationship between psychosocial status, acculturation and country of origin in mid-life Hispanic women: data from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN). Climacteric 2010;13:534–543. 10.3109/13697131003592713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Doyle L, McCabe C, Keogh B, Brady A, McCann M. An overview of the qualitative descriptive design within nursing research. J Res Nurs 2020;25:443–455. 10.1177/1744987119880234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cortés YI, Marginean V, Berry D. Physiologic and psychosocial changes of the menopause transition in US Latinas: a narrative review. Climacteric 2021;24:214–228. 10.1080/13697137.2020.1834529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cortés YI Duran M Marginean V, et al. Lessons learned in clinical research recruitment of midlife Latinas during COVID-19. Menopause 2022;29:883–888. 10.1097/GME.0000000000001983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bazargan M Loeza M Ekwegh T, et al. Multi-dimensional impact of chronic low back pain among underserved African American and Latino older adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18:7246. 10.3390/ijerph18147246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fillingim RB Slade GD Greenspan JD, et al. Long-term changes in biopsychosocial characteristics related to temporomandibular disorder: findings from the OPPERA study. Pain 2018;159:2403–2413. 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]