Learn more: PMC Disclaimer | PMC Copyright Notice

. 2024 Aug 30:22925503241276549. Online ahead of print. doi: 10.1177/22925503241276549

Abstract

Introduction: The characteristics, complications, and postoperative analgesic needs of patients with a recent or active history of recreational cannabis use have not been explored explicitly in plastic surgery. In this study, the characteristics, complications, and postoperative analgesic needs within a population of breast reduction patients who use and do not use recreational cannabis were compared. Methods: A retrospective cohort study was carried out on patients who underwent breast reduction between 2019 and 2023. Demographics, comorbidities, recreational cannabis use, postoperative opioid use, and postoperative complications were collected. Patients with a recent history (<1 month since last cannabis use) or current cannabis use were then compared to patients with no history of cannabis use. Results: In total, 340 patients were included, 88 (26%) patients had a history of cannabis use and 252 (74%) did not. Patients in the cannabis-using group were significantly younger than in the non-cannabis-using group (28 years vs 40 years, P < .01), and significantly more patients in the non-cannabis group had hypertension (20% vs 6% P < .01). More patients in the cannabis-using group had hematomas (5% vs 1%, P = .041) and fewer had t-point breakdown (4% vs 0%, P = .046), but these figures lost statistical significance on multiple logistic regression analysis after controlling for possible confounding factors including demographics and comorbidities (P > .05). There were no significant differences in proportions of opioid use or by doses of opioids, even when converted to oral morphine equivalents (P > .05). Conclusion: The analgesic needs, postoperative pain levels, and complications between cannabis-using and non-cannabis-using cohorts were similar. Counseling on substance use preoperatively should still be encouraged, especially in younger patients seeking reduction mammaplasty.

Introduction

Given its increasing legalization and use in society, the role of cannabis products in medicine has come under scrutiny. Cannabis, the species which includes the marijuana plant and the psychoactive component tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), has experienced widespread acceptance throughout the United States, particularly in response to research on safe use and possible therapeutic applications.1Currently, 33 states and the District of Columbia have legalized cannabis for recreational use.2Internationally, the World Health Organization estimates that 2.5% of the world’s population currently uses cannabis products for any number of purposes, including recreational and medical uses.3With this larger acceptance and use of cannabis products, almost 45 million people within the United States have reported to use some form of cannabis, the highest concentration of which is among 18 to 25-year-olds.4

Within the medical community, THC-containing products like cannabis have been regarded both as a recreational drug and an important means of analgesia for those with chronic pain. Multiple studies on patients with chronic pain, such as cancer patients, report mixed results with respect to cannabis products improving analgesic needs, and larger review articles have corroborated these ambiguous effects.5–7 Studies in surgical subspecialties have also shown mixed results in terms of postoperative analgesic needs and complications in patients with a history of cannabis use. Studies in neurosurgery have shown that patients with a history of cannabis use have higher average postoperative pain levels and required more analgesia, a similar result was found in gynecological surgery patients.8,9 Beyond pain control, cannabis-using patients who underwent cholecystectomy or appendectomy were found to have longer postoperative stays.10The data are varied due to study design, medical discipline, and population.

The impact of prior recreational cannabis on plastic surgery patients, however, is currently inconclusive. Reviews of the literature have found there is scant evidence on the impact of THC in this surgical population, with a call for more research to be done on plastic surgery patients in order to identify any preoperative, intraoperative, or postoperative risks associated with cannabis use.11,12 Based on aforementioned studies, there is a concern that patients who use cannabis products recreationally may have more pain postoperatively, and therefore present greater challenges to achieving adequate pain control, as well as more postoperative complications than those who do not use cannabis recreationally. Breast reduction is a common plastic surgery procedure that patients often undergo for a variety of reasons, including macromastia that causes musculoskeletal pain or skin irritation.13Increasing numbers of young patients are undergoing breast reduction and are usually medically optimized for surgery.14In addition, the postoperative course of this procedure is relatively standard. This study sought to determine the complication profile and immediate opioid-based postoperative analgesic needs of cannabis-using patients who have undergone breast reduction.

Methods

Following approval by the Institutional Review Board at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai (STUDY-22-01703), a retrospective cohort study was carried out on all patients who underwent breast reduction mammaplasty between 2019 and 2023. Informed consent was not required for this study. Recreational cannabis use, demographics, postoperative analgesia requirements, and 30-day postoperative complications (wound healing issues, tissue necrosis, infection, hematoma, and seroma) were collected. Cannabis use was characterized from preoperative anesthesia records on the day of surgery, with patients who had used cannabis consistently within one month defined as “cannabis-using” and those who never used cannabis as “non-cannabis-using”. In order to characterize pain, opioid-based analgesia given in the post anesthesia care unit before discharge was recorded and converted to oral morphine equivalents (OMEs), this was defined as the immediate postoperative period. Postoperative opioid-based analgesia included intravenous fentanyl and hydromorphone, and oral oxycodone, which were delivered based on patient-reported pain levels. Standard doses of fentanyl and hydromorphone were given for severe pain, and oral oxycodone was given for moderate pain. OMEs were calculated using conversion tables from Tan et al.15Patients of age <18 years, patients with a history of breast cancer, and patients who reported a remote history of cannabis use (>1 month since last use) were excluded.

Descriptive statistics of categorical variables were reported as frequencies and proportions (n,%). For continuous variables, normally distributed variables based on Shapiro-Wilk testing were reported as means and standard deviations (SD), and non-normally distributed variables were reported as median and interquartile range (IQR). Multiple logistic regression was carried out to evaluate the odds of postoperative outcomes and opioid use while controlling for possible confounding factors that could impact outcomes or were significantly different on univariate analysis, including age, self-identified race, spoken language, smoking status, comorbidities, intraoperative blood loss, and ASA status. Results were reported as odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). Statistical significance was set at P < .05. Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS statistics for Macintosh, Version 28.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY), and Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA).

Results

Baseline and Comparative Demographics and Comorbidities

Three-hundred forty patients were included in the study: 88 (26%) patients had a history of cannabis use and 252 (74%) patients had no history of cannabis use. Table 1 shows comparative demographics and comorbidities. The overall cohort was 100% female, with a median age of 35 years (IQR, 23 years) and a mean body mass index (BMI) of 30 kg/m2 (SD, 5 kg/m2). Three-hundred ten patients (91%) spoke English, 105 (31%) identified as White, followed by 95 as African American (28%). The majority of patients reported never smoking (79%), followed by being a former smoker (19%) or a current smoker (3%). In terms of comorbidities, 55 (16%) patients had hypertension, 42 (12%) had hyperlipidemia, 16 (5%) had diabetes mellitus. Comparative demographics and comorbidities revealed the median age of patients in the cannabis-using group was significantly younger than the non-cannabis-using group (28 years vs 40 years, P < .01), and significantly more patients in the non-cannabis-using group had hypertension (20% vs 5%, P < .01).

Table 1.

Comparative Demographics and Operative Characteristics.

| Variable | Total (n = 340) | Non-Cannabis-Using (n = 252) | Cannabis Using (n = 88) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR), years | 35 (23.47) | 40 (24) | 28 (9) | <.01 |

| Body Mass Index, mean (SD), kg/m2 | 29.75 (5.39) | 29.53 (5.39) | 29.70 (5.35) | .751 |

| Language, n (%) | <.001 | |||

| English | 310 (91.2%) | 223 (88.5%) | 88 (100%) | |

| Spanish | 29 (8.5%) | 29 (100%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Race, n (%) | .018 | |||

| White | 107 (31.5%) | 76 (30.2%) | 31 (35.2%) | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 45 (13.2%) | 38 (15.1%) | 7 (8.0%) | |

| Black/African American | 95 (27.9%) | 65 (25.8%) | 30 (34.1%) | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 10 (2.9%) | 7 (2.8%) | 3 (3.4%) | |

| Other/Unknown | 83 (24.4%) | 66 (26.2%) | 17 (19.3%) | |

| Smoking, n (%) | .097 | |||

| Never | 267 (78.5%) | 198 (78.6%) | 69 (78.4%) | |

| Former | 64 (18.8%) | 50 (19.8%) | 14 (15.9%) | |

| Current | 9 (2.6%) | 4 (1.6%) | 5 (5.7%) | |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 55 (16.2%) | 50 (19.8%) | 5 (5.7%) | <.01 |

| Hyperlipidemia, n (%) | 42 (12.4%) | 35 (13.9%) | 7 (8%) | .145 |

| Diabetes Mellitus, n (%) | 16 (4.7%) | 14 (5.6%) | 2 (2.3%) | .211 |

| Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, n (%) | 1 (0.3%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.1%) | .259 |

| Coronary Artery Disease, n (%) | 2 (0.6%) | 2 (0.8%) | 0 (0%) | .549 |

| Renal Disease, n (%) | 5 (1.5%) | 4 (1.6%) | 1 (1.1%) | .614 |

| Bleeding Disorder, n (%) | 5 (1.5%) | 4 (1.6%) | 1 (1.1%) | .619 |

| ASA Status, n (%) | .109 | |||

| 1 | 64 (20.1%) | 40 (17.2%) | 24 (27.6%) | |

| 2 | 232 (72.7%) | 172 (74.1%) | 60 (69%) | |

| 3 | 22 (6.9%) | 19 (8.2%) | 3 (3.4%) | |

| 4 | 1 (0.3%) | 1 (0.4%) | 0 (0%) |

Intraoperative Characteristics

Table 2 demonstrates intraoperative characteristics. One-hundred ninety patients (56%) in the study received a superomedial pedicle, 120 (35%) received an inferior pedicle. Median total resection weight was 1071 grams (IQR, 926 grams), and median estimated blood loss was 50 milliliters (IQR, 70 milliliters). Seventy-eight patients (23%) received concurrent liposuction of the breasts, and 192 patients (57%) had drains placed. Estimated blood loss was significantly different between groups, however, the median for each group was 50 milliliters (IQR, 70 milliliters, P = .022).

Table 2.

Intraoperative Characteristics.

| Variable | Total (n = 340) |

Non-Cannabis-Using (n = 252) | Cannabis Using (n = 88) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Resection Weight, median (IQR), grams | 1071 (925.75) | 1071 (913) | 1099 (1050) | .528 |

| Estimated Blood Loss, median (IQR), milliliters | 50 (70) | 50 (70) | 50 (70) | .022 |

| Pedicle Type, n (%) | .510 | |||

| Inferior | 120 (35.3%) | 85 (33.7%) | 35 (39.8%) | |

| Superomedial | 190 (55.9%) | 143 (56.7%) | 47 (53.4%) | |

| Other | 30 (8.8%) | 24 (9.5%) | 6 (6.8%) | |

| Liposuction of Breasts, n (%) | 78 (22.9%) | 62 (24.6%) | 16 (18.2%) | .217 |

| Drain Use, n (%) | 192 (56.5%) | 141 (56.0%) | 51 (58.0%) | .744 |

Postoperative Complications

Table 3 shows postoperative complications. Overall complications were low and not significantly different in each cohort (10% vs 8%, P = .587), the most common of which was t-point breakdown (3.2%). Comparatively, there was a statistically significantly lower rate of t-point breakdown in cannabis-using patients (0% vs 4%, P = .046), and a statistically significantly greater rate of hematomas in cannabis-using patients (5% vs 1%, P = .041). There was no difference in other complications, including wound dehiscence, fat necrosis, nipple necrosis, cellulitis, abscess, seroma, or revision surgery. After controlling for age, self-identified race, spoken language, hypertension status, smoking status, ASA status, and estimated blood loss, factors that were significantly different among groups (P < .05) or could conceivably impact certain outcomes, multiple logistic regression analysis showed the risk of any complication (OR 0.958, 95% CI 0.351-2.615, P = .934), wound dehiscence (OR 1.379, 95% CI 0.112-17.045, P = .802), fat necrosis (OR 0.322, 95% CI 0.033-3.170, P = .332), cellulitis or erythema (OR 1.791, 95% CI 0.366-0.750, P = .472), and hematoma (OR 7.394, 95% CI 0.822-66.473, P = .074) were not significantly increased or decreased in cannabis-using patients. Regression analyses for t-point breakdown, nipple necrosis, breast abscess, seroma, and revisions were not meaningful due to the very low rates of these complications.

Table 3.

Postoperative Complications.

| Variable, n (%) | Total (n = 340) |

Non-Cannabis-Using (n = 252) | Cannabis Using (n = 88) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any Complication | 32 (9.4%) | 25 (9.9%) | 7 (8%) | .587 |

| T-point breakdown | 11 (3.2%) | 11 (4.4%) | 0 (0%) | .046 |

| Wound Dehiscence | 5 (1.5%) | 4 (1.6%) | 1 (1.1%) | .614 |

| Fat Necrosis | 10 (2.9%) | 9 (3.6%) | 1 (1.1%) | .244 |

| Nipple Necrosis | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | N/A |

| Cellulitis/Erythema | 9 (2.6%) | 6 (2.4%) | 3 (3.4%) | .605 |

| Breast Abscess | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | N/A |

| Hematoma | 6 (1.8%) | 2 (0.8%) | 4 (4.5%) | .041 |

| Seroma | 7 (2.1%) | 7 (2.8%) | 0 (0%) | .114 |

| Complication Requiring Revision | 6 (1.8%) | 6 (2.4%) | 0 (0%) | .345 |

Immediate Postoperative Analgesic Use

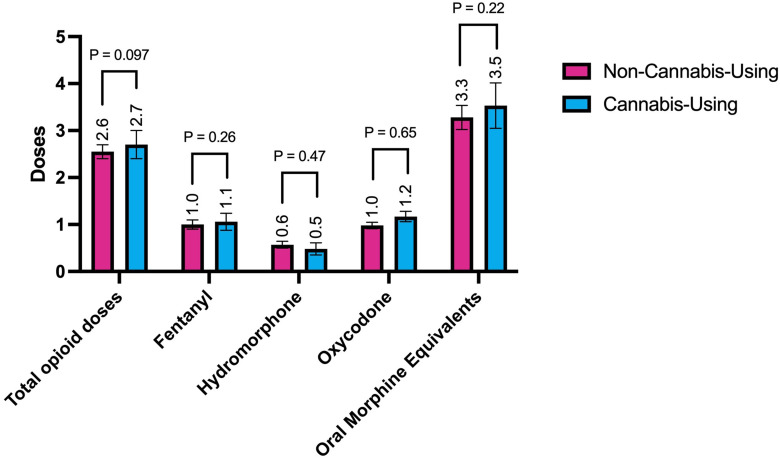

Two-hundred sixty-six patients (78%) required opioids for pain control in the immediate postoperative period, 196 patients (58%) received oxycodone for moderate pain, 134 (39%) received fentanyl for severe pain, and 83 (24%) received hydromorphone for severe pain (Table 4). There were no significant differences between rates of opioid consumption overall or by opioid type between cannabis-using and non-cannabis-using patients (Table 4). By mean opioid doses per patient, there was no statistically significant difference in total opioid doses in the immediate postoperative period (2.55 vs 2.70 doses, P = .097), or when converted to OMEs (3.28 vs 3.52, P = .215) (Figure 1). There was also no significant difference when stratified by opioid type, which included fentanyl given for severe pain (1.01 vs 1.06 doses, P = .264), hydromorphone also given for severe pain (0.55 vs 0.57 doses, P = .469), and oxycodone given for moderate pain (0.98 vs 1.17 doses, P = .649) (Figure 1). Controlling for the same factors as in the regression analysis for outcomes, multiple logistic regression analysis to evaluate the odds of postoperative opioid use revealed no increased or decreased odds of any opioid use (OR 0.808, 95% CI 0.426-1.534, P = .515), oxycodone use (OR 1.457, 95% CI 0.824-2.576, P = .196), hydromorphone use (OR 0.695, 95% CI 0.354-1.366, P = .291), or fentanyl use (OR 0.845, 95% CI 0.476-1.501, P = .566).

Table 4.

Comparative Opioid Use.

| Variable, n (%) | Total (n = 340) | Non-Cannabis-Using (n = 252) | Cannabis Using (n = 88) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any Opioid Use | 266 (78.2%) | 200 (79.4%) | 66 (75%) | .393 |

| Fentanyl Use | 134 (39.4%) | 101 (40.1%) | 33 (37.5%) | .670 |

| Hydromorphone Use | 83 (24.4%) | 66 (26.2%) | 17 (19.3%) | .196 |

| Oxycodone Use | 196 (57.6%) | 140 (55.6%) | 56 (63.6%) | .187 |

Figure 1.

Discussion

The present study aimed to evaluate the demographics, complications, and postoperative analgesia needs of patients undergoing breast reduction and who have a history of recreational cannabis use. While studies have evaluated non-plastic surgery patients for the impact of cannabis use on complications and analgesic needs, none have aimed to do so within plastic surgery itself. The present study found that cannabis-using patients did not have greater analgesic demands than non-cannabis-using patients in the immediate postoperative period. Furthermore, cannabis-using patients were significantly younger than non-cannabis-using patients, and complications between cannabis-using and non-cannabis using patients were not different except for the rate of hematomas and t-point breakdown, although the difference in hematomas lost significance on regression analysis, suggesting that possible confounding factors, including demographics and comorbidities, contribute to these outcomes beyond cannabis use alone.

This study found that a history of cannabis use does not significantly impact analgesic needs in the immediate postoperative period. Studies from other disciplines have shown mixed results, with some studies showing more analgesia requirements and higher pain scores among patients with a history of cannabis use, and other studies found the opposite.8–10 Analgesic needs among cannabis-using and non-cannabis-using patients continues to be a debate across specialties, and complicated by the fact that cannabis itself can act as analgesia for some patients. The literature generally supports the role of cannabinoids in their treatment of chronic pain; however, data for perioperative pain relief are lacking.16,17 The use of cannabis for the treatment of chronic pain has been regarded as an effective treatment. Studies have shown a considerable decrease in pain among these patients, and legalization of marijuana has decreased prescription pain medication use among some populations.18–20 Within surgery, studies in orthopedic total knee arthroplasties have found that there was a general trend associated with postoperative cannabis use decreasing the need for postoperative prescription analgesia such as opioids, although these studies did not reach statistical significance.21,22 Despite this, larger meta-analyses concluded that cannabis-based medications are not effective in the treatment of postoperative pain and recommended further investigation.7Even more, studies have shown an inverse relationship between cannabis use and chronic pain, that those with a history of cannabis use often experienced higher pain levels than those who did not have a history of cannabis use.23This study did not find significance in the role of recreational cannabis use among patients impacting postoperative analgesic needs; however, literature is lacking in this area and tends to be more focused on the use of cannabis products in the hospital setting as an alternative to other analgesic medications. The strongest evidence of therapeutic benefit of cannabis products includes chronic pain, chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, and muscle spasticity associated with multiple sclerosis.18,19 These aforementioned studies explored the impact of cannabis on pain in several settings, and collectively suggest that cannabis itself may be useful in decreasing pain in the postoperative period as an analgesic tool, but when used preoperatively for recreational purposes, it may make no difference in postoperative pain, or it may actually increase pain levels and analgesic needs. While the present study is limited in its ability to explore the impact of increasing cannabis use on postoperative analgesic use and pain, it is important for providers in the surgery care continuum to be aware of recreational cannabis use.

With respect to complications among cannabis-using patients, there was a greater rate of postoperative hematoma formation in the cannabis-using group, with about 5% of the cohort having a postoperative hematoma formation compared to 1% among non-users. This result was statistically significant on univariate analysis without controlling for confounding factors; however, the result became non-statistically significant after controlling for confounding factors, meaning the odds of hematoma formation may ultimately not be meaningfully increased in patients who use recreational cannabis. Nonetheless, postoperative hematoma formation is a serious complication that may require hospitalization or operative intervention, and is clinically relevant to discuss in patients who use recreational cannabis. Previous studies have shown increased anticoagulant effect of cannabis on patients who take anticoagulant medication. THC decreases the action of CYP2C19 and CYP2C9, which are responsible for the metabolism of anticoagulants such as warfarin and clopidogrel, respectively, thereby increasing their plasma levels and ultimately bleeding risk.24None of the patients who developed a postoperative hematoma in this study were taking anticoagulation medication or had bleeding disorders at the time of data collection. Beyond the effect of anticoagulant medication, a study by Yoo et al. on patients receiving percutaneous coronary intervention were found to have a significantly increased risk of bleeding during admission if they had used THC-containing products prior to their procedure.25Although these hypotheses are still experimental, THC may influence postoperative bleeding. Additionally, while the difference in hematoma formation between cohorts in this study was small but significant, this is still an important consideration when evaluating surgical qualifications for patients seeking elective procedures, especially given the morbidity and cost associated with a postoperative hematoma. In addition, wound healing problems were similar between groups except for t-point breakdown, which was significantly lower in the cannabis-using cohort. T-point breakdown can occur due to a variety of reasons such as mechanical breakdown and wound-related healing problems, and perhaps having a history of cannabis use is beneficial in promoting better wound healing. Wound healing progress was not able to be assessed between the two cohorts; however, studies have shown the role of cannabis in aiding wound healing, particularly in mediating vasodilation and fibroblast activation, as well as regulating differentiation of epidermal keratinocytes.26,27 THC, and other components of the cannabis plant such as cannabidiol (CBD), is also anti-inflammatory according to some studies.26,27

In terms of the demographics and characteristics of THC-using patients, the patients in the present study were significantly younger, which reflects a national trend of cannabis-using patients being on average younger than those who do not use cannabis.28Also within this population, recreational cannabis use far exceeds that of medical cannabis use, with about 89% of reported cannabis use being recreational.18Generally, the highest concentration of cannabis users are between 18 and 25 years old.4In present study the median age of cannabis-using patients was 30 years old. Other important demographics of cannabis users include level of education, with those having only a high school education being more likely to use THC products, as well as patients with chronic illness such as cancer and other conditions.18

The present study has limitations. Due to the retrospective nature, postoperative pain could not be assessed systematically, and instead opioid requirements were utilized as an objective proxy. In addition, analgesic use intraoperatively and after discharge was not able to be evaluated in this study, as the clinical decisions by anesthesiologists intraoperatively to administer opioids were heterogeneous, and outpatient pain medication use was difficult to track, respectively. Variables such as wound healing progress and postoperative nausea were also not able to be explored due to the retrospective nature of the study. Finally, despite its widespread cultural and legal acceptance, there may still be a perceived stigma regarding THC use and patients may have chosen to modify or not share their THC use history with providers due to fears of disapproval. Future directions include exploring these additional variables and conducting a prospective study.

Conclusion

The present study suggests that there is no difference in postoperative analgesia requirements in patients who use cannabis, but cannabis use may confer a higher risk of postoperative hematoma, and a lower risk of t-point breakdown. Performing a comprehensive recreational drug use history is essential to ensuring patient safety and counseling throughout the surgical process, but a history of recreational cannabis use should not preclude patients from undergoing breast reduction surgery.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Peter E Shamamian was responsible for conceptualization, data collection, data analysis, manuscript writing, and manuscript review. Daniel Y Kwon was responsible for data collection, data analysis, and manuscript review. Olachi Oleru and Nargiz Seyidova were responsible for conceptualization, data analysis, and manuscript review. Esther Kim, Simeret Genet, Abena Gyasi, and Carol Y Wang were responsible for data collection and manuscript review. Peter W Henderson was responsible for conceptualization and manuscript review.

Author Olachi Oleru was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) TL1TR004420 NRSA TL1 Training Core in Transdisciplinary Clinical and Translational Sciences (CTSA).

Ethical Statements:

-

This study received approval from the Institutional Review Board at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai (STUDY-22-01703)

-

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

-

This study did not require informed consent

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Peter E. Shamamian https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7904-8004

Olachi Oleru https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0327-2613

References

- 1.Center PR. U.S. public opinion on legalizing marijuana, 1969–2018. 2019. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/06/26/facts-about-marijuana/ft_19-06-26_marijuana_us-public-opinion-on-legalizing-marijuana-1969-2018/

- 2.Legislatures NCoS. State medical marijuana laws. http://www.ncsl.org/research/health/state-medical-marijuana-laws.aspx

- 3.Organization WH. Management of substance abuse: cannabis. https://www.who.int/substance_abuse/facts/cannabis/en/

- 4.Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: results from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. 2019.

- 5.Blake A, Wan BA, Malek L, et al. A selective review of medical cannabis in cancer pain management. Ann Palliat Med. 2017;6(Suppl 2):S215–s222. doi: 10.21037/apm.2017.08.05 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meng H, Dai T, Hanlon JG, et al. Cannabis and cannabinoids in cancer pain management. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2020;14(2):87–93. doi: 10.1097/spc.0000000000000493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aviram J, Samuelly-Leichtag G. Efficacy of Cannabis-based medicines for pain management: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pain Physician. 2017;6(6):E755–e796. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dupriest K, Rogers K, Thakur B, et al. Postoperative pain management is influenced by previous Cannabis use in neurosurgical patients. J Neurosci Nurs. 2021;53(2):87–91. doi: 10.1097/jnn.0000000000000577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wiseman LK, Mahu IT, Mukhida K. The effect of preoperative Cannabis use on postoperative pain following gynaecologic oncology surgery. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2022;44(7):750–756. doi: 10.1016/j.jogc.2022.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderson SR, Wimalawansa SM, Markov NP, et al. Cannabis abuse or dependence and post-operative outcomes after appendectomy and cholecystectomy. J Surg Res. 2020;255:233–239. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2020.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edalatpour A, Attaluri P, Larson JD. Medicinal and recreational marijuana: Review of the literature and recommendations for the plastic surgeon. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2020;8(5):e2838. doi: 10.1097/gox.0000000000002838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stephens KL, Heineman JT, Forster GL, et al. Cannabinoids and pain for the plastic surgeon: What is the evidence? Ann Plast Surg. 2022;88(5 Suppl 5):S508–s511. doi: 10.1097/sap.0000000000003128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sachs DS, D K. Breast reduction. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2023. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nuzzi LC, Firriolo JM, Pike CM, et al. Complications and quality of life following reduction mammaplasty in adolescents and young women. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;144(3):572–581. doi: 10.1097/prs.0000000000005907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tan S, Lee E, Lee S, et al. Morphine equianalgesic dose chart in the emergency department. J Educ Teach Emerg Med. 2022;7(3):L1–L20. doi: 10.21980/j8rd29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stewart C, Fong Y. Perioperative Cannabis as a potential solution for reducing opioid and benzodiazepine dependence. JAMA Surg. 2021;156(2):181–190. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2020.5545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davidson EM, Raz N, Eyal AM. Anesthetic considerations in medical cannabis patients. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2020;33(6):832–840. doi: 10.1097/aco.0000000000000932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Academies of Sciences E, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice; Committee on the Health Effects of Marijuana. The Health Effects of Cannabis and Cannabinoids: The Current State of Evidence and Recommendations for Research. National Academies Press; 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whiting PF, Wolff RF, Deshpande S, et al. Cannabinoids for medical use: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Jama. 2015;313(24):2456–2473. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.6358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bradford AC, Bradford WD. Medical marijuana laws reduce prescription medication use in medicare part D. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(7):1230–1236. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hickernell TR, Lakra A, Berg A, et al. Should cannabinoids be added to multimodal pain regimens after total hip and knee arthroplasty? J Arthroplasty. 2018;33(12):3637–3641. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2018.07.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Azim S, Nicholson J, Rebecchi MJ, et al. Endocannabinoids and acute pain after total knee arthroplasty. Pain. 2015;156(2):341–347. doi: 10.1097/01.j.pain.0000460315.80981.59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boehnke KF, Scott JR, Litinas E, et al. High-Frequency medical Cannabis use is associated with worse pain among individuals with chronic pain. J Pain. 2020;21(5-6):570–581. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2019.09.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Greger J, Bates V, Mechtler L, et al. A review of Cannabis and interactions with anticoagulant and antiplatelet agents. J Clin Pharmacol. 2020;60(4):432–438. doi: 10.1002/jcph.1557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yoo SGK, Seth M, Vaduganathan M, et al. Marijuana use and in-hospital outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention in Michigan, United States. JACC Cardiovasc Interventions. 2021;14(16):1757–1767. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2021.06.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tóth KF, Ádám D, Bíró T, et al. Cannabinoid signaling in the skin: Therapeutic potential of the “C(ut)annabinoid” system. Molecules. 2019;24(5):918. doi: 10.3390/molecules24050918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Palmieri B, Laurino C, Vadalà M. A therapeutic effect of cbd-enriched ointment in inflammatory skin diseases and cutaneous scars. Clin Ter. 2019;170(2):e93–e99. doi: 10.7417/ct.2019.2116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carlini BH, Schauer GL. Cannabis-only use in the USA: Prevalence, demographics, use patterns, and health indicators. J Cannabis Res. 2022;4(1):39. doi: 10.1186/s42238-022-00143-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]